Difference between revisions of "Ulysses S. Grant"

(→Other Meetings and Functions: photo) |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

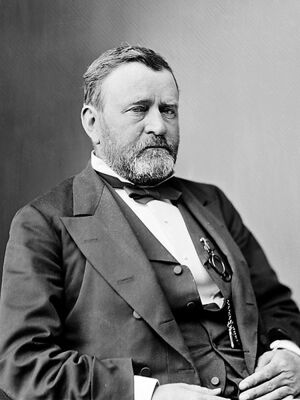

[[Image:Ulysses Grant.jpg|right|thumb|300px|Ulysses S. Grant. Photograph taken c. 1870-1880.]] | [[Image:Ulysses Grant.jpg|right|thumb|300px|Ulysses S. Grant. Photograph taken c. 1870-1880.]] | ||

| − | *''Born: [[1822]]'' | + | *''Born: [[1822]], April 27'' |

| − | *''Died: [[1885]]'' | + | *''Died: [[1885]], July 23'' |

| − | *''Titles: General-in-Chief of the Union Army (1864- | + | *''Titles: General-in-Chief of the Union Army (1864-1869), President of the United States (1869-1877)'' |

Ulysses S. Grant, American Civil War hero and two-term President, visited Japan from June 21 to September 3, 1879, the last leg of a two and a half year global tour. Though no longer President at this time, and traveling purely as a private citizen, not as an official representative of the United States in any respect, his visit was viewed by the [[Meiji government]] as an important diplomatic opportunity. | Ulysses S. Grant, American Civil War hero and two-term President, visited Japan from June 21 to September 3, 1879, the last leg of a two and a half year global tour. Though no longer President at this time, and traveling purely as a private citizen, not as an official representative of the United States in any respect, his visit was viewed by the [[Meiji government]] as an important diplomatic opportunity. | ||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

When he met with Prince Kung, the prince explained to Grant that the Chinese sought not to annex the Ryukyus themselves, but to restore the kingdom, along with its [[tribute|tributary]] status. He assured the former president that China was not interested in the domestic affairs of the island kingdom, nor which other countries it made agreements with and paid tribute to, but only that the [[Chinese investiture envoys|investiture rituals and relationship]] between China and Ryûkyû be restored and continued, and that Japan rescind any claims to exclusive sovereignty over the islands. | When he met with Prince Kung, the prince explained to Grant that the Chinese sought not to annex the Ryukyus themselves, but to restore the kingdom, along with its [[tribute|tributary]] status. He assured the former president that China was not interested in the domestic affairs of the island kingdom, nor which other countries it made agreements with and paid tribute to, but only that the [[Chinese investiture envoys|investiture rituals and relationship]] between China and Ryûkyû be restored and continued, and that Japan rescind any claims to exclusive sovereignty over the islands. | ||

| − | Viceroy Li similarly aimed to convince Grant of China's relatively altruistic motives in seeing the kingdom restored as an independent power, and denied any Chinese intentions or desires to annex it. He explained that China had never claimed sovereignty over the islands, only a suzerain relationship and close ties involving tribute, investiture, the strong involvement of people of Chinese descent in education and government in Ryûkyû, and a system by which Ryukyuans studied and sojourned in China. Grant was also told that the Ryukyuans preferred their association with China, a sentiment which would have been backed up by recent letters from Shô Tai in exile in Tokyo requesting Chinese assistance, and by those of Ryukyuan official [[Kochi Chojo|Kôchi Chôjô]] who was resident in China at this time, though it is unclear if Grant would have seen these letters or met with Kôchi ''[[ueekata]]''. | + | Viceroy Li similarly aimed to convince Grant of China's relatively altruistic motives in seeing the kingdom restored as an independent power, and denied any Chinese intentions or desires to annex it. He explained that China had never claimed sovereignty over the islands, only a suzerain relationship and close ties involving tribute, [[investiture]], the strong involvement of people of Chinese descent in education and government in Ryûkyû, and a system by which Ryukyuans studied and sojourned in China. Grant was also told that the Ryukyuans preferred their association with China, a sentiment which would have been backed up by recent letters from Shô Tai in exile in Tokyo requesting Chinese assistance, and by those of Ryukyuan official [[Kochi Chojo|Kôchi Chôjô]] who was resident in China at this time, though it is unclear if Grant would have seen these letters or met with Kôchi ''[[ueekata]]''. |

Grant was, however, unconvinced by Kung's altruistic-seeming claims to not have an interest in the kingdom's affairs or in seeing the tributary relationship restored. Additionally, Grant is said to have had great admiration for Japan's military modernization efforts, and to have believed that if it came down to war, Japanese victory would have been inevitable<ref name=Kerr>Kerr.</ref>. | Grant was, however, unconvinced by Kung's altruistic-seeming claims to not have an interest in the kingdom's affairs or in seeing the tributary relationship restored. Additionally, Grant is said to have had great admiration for Japan's military modernization efforts, and to have believed that if it came down to war, Japanese victory would have been inevitable<ref name=Kerr>Kerr.</ref>. | ||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

Though he had visited a great many countries during his two and a half year tour, it is said that Grant truly held a special admiration, sympathy, and affection for Japan, which he saw as a rising power in the East, capable of great things<ref name=chang/>. | Though he had visited a great many countries during his two and a half year tour, it is said that Grant truly held a special admiration, sympathy, and affection for Japan, which he saw as a rising power in the East, capable of great things<ref name=chang/>. | ||

| − | Grant fell ill in 1885, and died later that year. During his illness, the Japanese ambassador to Washington was sent by the Emperor to visit the former president at his home in | + | Grant fell ill in 1885, and died later that year. During his illness, the Japanese ambassador to Washington was sent by the Emperor to visit the former president at his home in New York City on at least four occasions; Grant focused, as well, in those last months of his life, on composing his memoirs.<ref>Plaque on-site at his former home at 3 East 66th St, where he lived from [[1881]] until 1885.</ref> |

During discussions surrounding the composition of the [[Meiji Constitution]] in [[1889]], the Meiji Emperor is said to have drawn heavily upon Grant's advice<ref name=chang/>. | During discussions surrounding the composition of the [[Meiji Constitution]] in [[1889]], the Meiji Emperor is said to have drawn heavily upon Grant's advice<ref name=chang/>. | ||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| − | [[Category:Meiji Period]] | + | [[Category:Meiji Period|Grant]] |

| − | [[Category:Foreigners]] | + | [[Category:Foreigners|Grant]] |

Latest revision as of 11:52, 31 March 2018

- Born: 1822, April 27

- Died: 1885, July 23

- Titles: General-in-Chief of the Union Army (1864-1869), President of the United States (1869-1877)

Ulysses S. Grant, American Civil War hero and two-term President, visited Japan from June 21 to September 3, 1879, the last leg of a two and a half year global tour. Though no longer President at this time, and traveling purely as a private citizen, not as an official representative of the United States in any respect, his visit was viewed by the Meiji government as an important diplomatic opportunity.

Japan at this time was struggling to present itself to the world as a fully modern nation, equal to the great Western powers. It sought revision of a number of Unequal Treaties signed in the Bakumatsu period, and was embroiled at the time in a dispute with China over the Ryukyu Islands. Though in no position to make formal statements on behalf of the United States, nor promise any official action, Grant expressed sympathy for Japan's situation vis-a-vis the treaties, assured the Japanese officials with whom he was speaking of the US policy of supporting a strong Asia against European encroachment, and spoke out against those governments which, unlike that of the US, outright refused to even consider renegotiation of the treaties. He pushed for Japan to seek to resolve the Ryukyu situation diplomatically and peacefully.

Through his advice on these and other matters, Grant played an important role in shaping the resolution of these matters, and, some would argue[1], was a notable influence upon the Meiji Emperor and Meiji government officials, through whom his advice helped shape domestic and foreign policy, as well as the Meiji Constitution. In addition, it has been said[1] that Grant's behavior and comportment, as well as his words, earned him and the United States great respect and gratitude among the ministers and officials of the Japanese government.

Grant in China

Former President Grant stayed in China for a time in early or mid-1879, along with his family and a few others. During this time he was wined and dined, and met with Viceroy Li Hongzhang in Tientsin on at least one occasion. As the Guangxu Emperor was only eight years old at the time, the former president was not granted an Imperial audience, but met with the Imperial regent Prince Kung twice, in Peking.

Japan abolished the Ryûkyû Kingdom and annexed its territory as Okinawa prefecture in March to May that year, as a preemptive measure against Chinese actions. Though this angered China, flying in the face of its requests of Tokyo in the matter, it also made Chinese efforts to claim Okinawa as its own more difficult, as the two countries had signed a commercial treaty in 1871 promising to respect one another's territorial sovereignty, and the former kingdom was now Japanese territory. This would also, in theory, make it more difficult for Grant, or the leaders of any of the major Western powers, to side with China in this matter.

Though Grant was traveling as a private citizen and, as a former president, wielded no real political authority or power, Li and Kung sought his support in the Ryûkyû dispute as something they could leverage as the symbolic support of the United States. After meeting with Viceroy Li in Tientsin and discussing the matter, Grant told Li that he would meet with the Japanese, hear their side of the story, and then make every effort he could, as a private citizen with no formal political power, to ensure the peaceful resolution of the dispute.

When he met with Prince Kung, the prince explained to Grant that the Chinese sought not to annex the Ryukyus themselves, but to restore the kingdom, along with its tributary status. He assured the former president that China was not interested in the domestic affairs of the island kingdom, nor which other countries it made agreements with and paid tribute to, but only that the investiture rituals and relationship between China and Ryûkyû be restored and continued, and that Japan rescind any claims to exclusive sovereignty over the islands.

Viceroy Li similarly aimed to convince Grant of China's relatively altruistic motives in seeing the kingdom restored as an independent power, and denied any Chinese intentions or desires to annex it. He explained that China had never claimed sovereignty over the islands, only a suzerain relationship and close ties involving tribute, investiture, the strong involvement of people of Chinese descent in education and government in Ryûkyû, and a system by which Ryukyuans studied and sojourned in China. Grant was also told that the Ryukyuans preferred their association with China, a sentiment which would have been backed up by recent letters from Shô Tai in exile in Tokyo requesting Chinese assistance, and by those of Ryukyuan official Kôchi Chôjô who was resident in China at this time, though it is unclear if Grant would have seen these letters or met with Kôchi ueekata.

Grant was, however, unconvinced by Kung's altruistic-seeming claims to not have an interest in the kingdom's affairs or in seeing the tributary relationship restored. Additionally, Grant is said to have had great admiration for Japan's military modernization efforts, and to have believed that if it came down to war, Japanese victory would have been inevitable[2].

Finally, Li addressed the strategic importance of the islands, and the possibility, should Japan maintain control of Ryûkyû, that Japan could block Chinese access to the Pacific. He also asserted to Grant that if Japan were to maintain control of Ryûkyû, it would not be long before it sought control of Taiwan and Korea as well.

Grant is said to have simply listened, promising to take into consideration all that Li and Kung had told him, that he would also take into account what the Japanese had to say, and volunteered that he might serve as arbiter or mediator should it be required to achieve a peaceful resolution.

Preparations and Reception in Japan

During their stay in Japan, Grant and his wife were given a reception matching or exceeding those given them elsewhere throughout their journey. Preparations began to be made six months before their arrival.

Prominent businessmen Shibusawa Eiichi and Iwasaki Yanosuke each contributed several thousand yen[3] to the effort, and a committee of government officials was established to organize the receptions for both the Grants, and for two European princes who would visit Japan the same year. A recommendation to receive General Grant as though he were a royal prince earned immediate approval. Yoshida Kiyonari, the Japanese ambassador to Washington who had served during Grant's time in office, was recalled, and made use of his familiarity with the Grants personally, as well as with American customs, to play an important role in the effort. The former President was escorted to official functions by Yoshida and Date Munenari, while Ishibashi Munakata and Tateno Gôzô of the Imperial Household attended to his accommodations.

A visit by the Duke of Edinburgh ten years prior had resulted in the remark, by one of the British nobles associated with the visit, that they might have much preferred to stay in a daimyo's mansion or the like; the Japanese had been quite determined to provide Western-style accommodations, and had produced something which apparently did not meet the Duke's standards. Such remarks had had no effect on the Japanese determination to see their own lavish aristocratic mansions as indicative of a backwards or uncivilized society, and to provide General Grant with Western-style accommodations in order to prove Japan a modern and civilized nation. No Western-style hotels yet existed in Japan, though some structures within Imperial and noble residences had been modified to somewhat imitate Western style. The Enryôkan, originally constructed by the shogunate as a naval academy, was quickly renovated to serve as the residence for both the Grants and the visiting European princes. A set of Western-style silverware, emblazoned with the Imperial chrysanthemum crest, was commissioned specifically for this purpose, and an Imperial jinrikisha was sent down to Nagasaki to meet the General and his wife.

Grant and his wife arrived in Nagasaki aboard the USS Richmond, on June 21 1879. They were accompanied by their son, and by John Russell Young, a New York Herald reporter who had been documenting the Grants' trip, and who was introduced to the Japanese as Grant's secretary. After a brief stay in Nagasaki, filled with tours of the city and formal receptions and speeches, the party boarded the Richmond once more on June 26 and set sail for Yokohama. The Grants had originally intended to visit a number of other areas, including Hyôgo, Osaka, Nara, and Kyoto, but despite elaborate and expensive receptions prepared for them in these locales, on account of a widespread cholera epidemic, the Japanese officials impressed upon their guests that the itinerary ought to be modified, and that the ship ought to journey directly to Yokohama.

The party arrived in Yokohama on July 3, where they were received by a number of officials including Iwakura Tomomi; they then traveled to Tokyo aboard a train set aside for this purpose. Nogi Maresuke headed a battalion of guards lining the streets between Shinbashi Station and the Enryôkan, and the Grants were greeted with an elaborate and enthusiastic welcoming ceremony. Pictures, pamphlets and a wide variety of other publications and ephemera circulated depicting or describing the former president, and his military exploits.

The following day, on July 4, a date consciously and intentionally chosen by the Emperor or his advisors, General Grant was granted an audience with the Meiji Emperor.

The following two weeks of Grant's stay in Japan was filled with receptions, dinner parties, notable guests both Western and Japanese, and a number of activities and events which would prove historic firsts. Grant, already the first President of the United States, sitting or otherwise, to visit Japan, was among the first Westerners to view a Noh performance, and the first Westerner to be granted a "popular reception ... by the Japanese populace"[4]. On July 16, he was treated to a performance of Gosannen Ôshû Gunki at the Shintomi-za, relating events in his life metaphorically through a tale set in the 11th century, with Minamoto no Yoshiie as the metaphorical stand-in for General Grant. He then formally presented the owner of the theater, Morita Kanya XII, with a stage curtain, which was received as a great honor.

The Ryûkyû Matter

It was during his stay in Nikkô[5] from July 17 to 31 that Grant set to the task of considering and discussing the Ryukyu dispute.

On July 22, Grant met with Minister of War Saigô Tsugumichi, Minister of the Interior Itô Hirobumi, and Yoshida, at his Nikkô inn. He advised the Japanese to seek a peaceful resolution, and to negotiate directly with China, without any third parties which might complicate negotiations and pursue their own goals. He also advised that a Sino-Japanese War would benefit the European powers which sought to further exploit a weakened Asia.

Itô expressed the Japanese view that Ryûkyû had long had a close relationship with Japan, that China's claims of sovereignty were patently outrageous, and that Japan would never seek to seize territories which were indisputably Chinese. He assured Grant that the government would take his advice into consideration, and thanked him for it. Grant, meanwhile, volunteered to advise the Chinese as well, if necessary.

Grant related to the Emperor on August 10, in the Nakajima Tea House at Hama Rikyû, what he had learned of Chinese attitudes on the matter. He expressed that the Chinese felt they were not receiving due respect as a sovereign power on this matter, but that the Chinese were open to negotiation and were not bent on war. He recommended the islands be divided, relating that one of China's chief concerns was that its access to the Pacific not be blocked, and again suggested to the Emperor that no European power introduced as a third-party in the negotiations (or war) would truly work to benefit the interests of either China or Japan, but only its own predatory, imperialistic interests.

Three days later, Grant wrote a formal letter to both Iwakura Tomomi and the Chinese Prince Kung, suggesting that China rescind certain threatening missives it had sent to Japan, that both countries appoint representatives to enter into negotiations with one another, and that neither country invite a foreign power into the negotiations, but that an individual arbiter, whose decisions would be honored as binding by both parties, might be appointed should the negotiations reach an impasse.

Grant would eventually leave Japan before the matter was resolved, though negotiations went forward in 1880 and war was averted, at least for the time being.

Other Meetings and Functions

During his Imperial audience on August 10, with Yoshida as interpreter and Prince Sanjô as the only other person present, Grant explicated his views on a wide range of matters, at the request of the Emperor. These included views on the possible revision of the Unequal Treaties, the foreign policy aims of the European powers, and popular suffrage. In the course of this meeting, he offered some advice on economic policy, specifically in recommending an increase of certain tariffs, so as to protect native industries and ease the tax burden on the Japanese people; for this, treaty revision was necessary, however. The matter of the implementation of popular suffrage, and of governance by popularly-elected assembly, was also discussed; Grant expressed the ultimate superiority of democratic forms of government, but warned against implementing it too quickly or hastily, as this could lead to chaos. Grant also advised that Japan should avoid borrowing money from foreign nations.

Both in discussions with the Emperor and Japanese officials, and in his private letters to his daughter, Grant expressed a strong distaste for the kind of Orientalist and racist attitudes espoused by the vast majority of Westerners towards the Japanese.

Popularly organized receptions and events, which had continued throughout Grant's stay in Japan, reached a climax with a festival in Ueno Park on August 25 which was attended by the Emperor.

Though he had never before during his time in Japan prepared a speech ahead of time, he did so for his official farewell address on August 30, before departing Japan on September 3, 1879.

Post-Japan

Though he had visited a great many countries during his two and a half year tour, it is said that Grant truly held a special admiration, sympathy, and affection for Japan, which he saw as a rising power in the East, capable of great things[1].

Grant fell ill in 1885, and died later that year. During his illness, the Japanese ambassador to Washington was sent by the Emperor to visit the former president at his home in New York City on at least four occasions; Grant focused, as well, in those last months of his life, on composing his memoirs.[6]

During discussions surrounding the composition of the Meiji Constitution in 1889, the Meiji Emperor is said to have drawn heavily upon Grant's advice[1].

A monument in his honor was erected in Ueno Park in 1929, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of his visit, at the site where he and Mrs. Grant had planted two trees. A special memorial service was held at this site in 1935, on the 50th anniversary of Grant's death. Since 1946, special memorial services have been held at this site, in Grant's honor, every year on Memorial Day.

References

- Chang, Richard. "General Grant's 1879 Visit to Japan." Monumenta Nipponica 24:4 (1969). pp373-392.

- Kerr, George. Okinawa: The History of an Island People. Revised Edition. Boston: Tuttle Publishing, 2000. pp376, 383-390, passim.

- "Ulysses S. Grant." WhiteHouse.gov. Accessed 4 January 2010.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Chang.

- ↑ Kerr.

- ↑ At the time, the yen-dollar exchange rate was roughly 1:1. The total expenditure by government and business leaders in excess of 68,000 yen on receptions, functions, accommodations, travel, etc for the Grants was roughly equal to $60,336 in 1879 US dollars.

- ↑ Chang. p379.

- ↑ It is said that when encouraged by his Japanese escorts to cross the famous Shinbashi (神橋), a privilege restricted to those of royal or imperial blood, he declined. Historian Richard Chang argues the importance of anecdotes such as these in showing the humility of Gen. Grant and indicating one of the key elements of his attitude, approach, and behavior which earned him great respect at a time when Japan perceived the US, and all major Western powers, as arrogant and domineering.

- ↑ Plaque on-site at his former home at 3 East 66th St, where he lived from 1881 until 1885.