Ryukyuan religion

Buddhism, Shinto, Confucianism, and Chinese folk religion (e.g. Tenpi worship) were all introduced into the Ryûkyû Islands in the premodern period, and had considerable impacts upon local religious beliefs and practices, particularly among the elites, and particularly in the central region of Okinawa Island. However, Ryûkyû is also home to its own native/indigenous religion, a set of animist beliefs and practices which many suggest likely grew out of similar or shared origins with Japanese Shinto, though others argue strongly that such ideas have colonialist and Orientalist origins and work to deny or erase Ryukyuan distinctiveness.[1]

The native religion does not have a set name. Though some use terms such as "nirai kanai worship," this really only refers to one aspect of the complex of spiritual/religious traditions and beliefs. Some use the term "Ryûkyû Shintô," either seeing it as an innocent term referring to the "Ryukyuan way of the gods," or, as native Japanese-language speakers and Japanese citizens raised in a heavily Japanese-influenced environment, simply thinking of it as the Ryukyuan version of (or equivalent of) Shinto, though many scholars and indigenous activists rail against this notion, calling the application of Japanese terms and categories to Ryukyuan culture a colonialist imposition - a rewriting of Ryukyuan history and culture to subordinate it to Japanese categories and understandings.[2]

The Ryûkyû Shintô ki ("Record of the Ways of the Gods in Ryûkyû") written by the Buddhist monk Taichû in 1605 indicates that Ryûkyû's native religion takes two deities, Shinerikyo and Amamikyo as the creator deities. They created the lords, noro (priestesses), and common people, as well as the new storm gods Kisomamon. Writing, specifically the "ten stems and twelve branches," was given to the people by Heaven.[3][4]

Sacred Spaces

Like mainland Japanese Shinto, the native Ryukyuan religion is centered in large part around naturally sacred spaces. In Ryûkyû, these are called uganju, and include sacred springs, small roadside altars, home altars, and sacred sites known as utaki; utaki most often take the form of sacred groves of trees, rock outcroppings, or clearings amongst the trees. While some are marked off by stone walls and gates, others simply feature small stone markers at the center of the site. Sefa utaki in southern Okinawa is considered the most sacred on the island, though Sonohyan utaki on the site of Shuri castle, being associated with the king, is also a highly sacred site. Certain islands and peaks are also sacred, Kudaka Island being perhaps the most important. Finally, as in many Pacific Islander religions, there is a belief in a land of the gods somewhere across the sea, from which sacredness emanates. In Ryûkyû, this land is called nirai kanai.[5] Miruku, a Ryukyuan form of the Buddha Maitreya (J: Miroku), is said to come from nirai kanai bringing yugafû (good fortune); this is reenacted in numerous island festivals, with a villager often dressing as Miruku and paddling to shore from the sea.

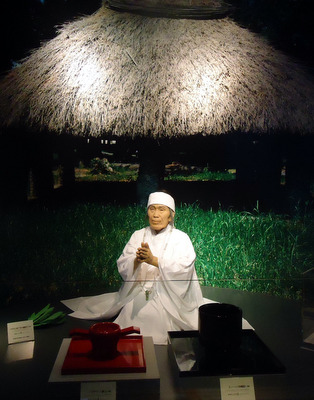

In the Amami Islands, villages often had an open space known as a myaa (みゃー) in the center of the village, within which a hut known as an ashage or toneya was built to serve as a site for various ceremonial or spiritual activities performed by the villagers, or by the noro (priestesses) of the village on their behalf. It was also a place where preparations for festivals and other larger ceremonies could be conducted, and where fires could be safely started and managed, away from homes. Though most ashage or toneya were traditionally straw-thatched huts, many villages today use modern concrete kôminkan ("public hall") buildings for this purpose.[6]

Amami is also home to sacred mountains known as kamiyama, linked to villages by narrow paths known as kami michi (spirit paths, or gods' roads). A typical kami michi may have been about one meter wide. It was traditionally believed that gods came from across the ocean and down the mountains in the 2nd month (of the traditional lunar calendar) each year to reside for a time in the village, returning in the 4th month.[7]

Religious Hierarchy

Women were traditionally believed to be more spiritually powerful than men, and men more spiritually vulnerable, an idea or belief system known as onarigami or unarigami. As a result, the most prominent and significant religious figures in the kingdom were priestesses. In local communities, too, it was typically women who performed rituals and ceremonies, including for the spiritual protection of the community. Though practices differed across the archipelago, local priestesses (noro) often wore white robes, necklaces of large stones (sometimes including magatama beads), and sacred headdresses or lei-like necklaces made from vines.[8]

Though organized somewhat more loosely in earlier times, in the late 15th century, King Shô Shin formalized the priestesses into a kingdom-wide hierarchy, linking them more closely to the royal court; though still quite powerful, the religious establishment thus represented somewhat less of a political threat. This new hierarchy was headed by the kikoe-ôgimi, typically the king's sister, who was responsible for providing spiritual protection for the king and kingdom, and overseeing some of the most important royal rituals. She also oversaw the entire hierarchy of priestesses, and along with the king was in charge of appointing women to become priestesses within the hierarchy.[9] Directly below the kikoe-ôgimi were the Oamushirare, three high priestesses who each oversaw one-third of the utaki, and one-third of the noro (priestesses) of the kingdom. Beneath them, then, were the noro, each of whom oversaw the utaki and spiritual affairs of a village or magiri (district); each village or magiri typically had several noro. Shamanesses called yuta were significantly less powerful, but were also not strictly overseen within the hierarchy.[10]

Deities

In addition to the creator deities Shinerikyo and Amamikyo, the sun (O: tiida) was also of great significance, and the king was considered "the son of the sun" (太陽子, tedako). A sacred hearth deity was also maintained, at Shuri castle by the kikoe-ôgimi for the whole kingdom, for each individual village by the local noro, and in each individual home as well.[11]

A great diversity of deities or spirits are worshipped additionally in many Ryukyuan communities, in ceremonies, rituals, and festivals which differ, sometimes quite considerably, from place to place. "Visiting spirits," known as raihôjin (来訪神) in Japanese, form a particularly prominent portion of these celebrations and ceremonies. Miruku, discussed above, is perhaps the most widely-known and widely-worshipped of these "visiting" deities. Others include:[12]

- the ancestral angama spirits (ushumai the grandfather and nmii the grandmother) of Ishigaki Island, who visit every house on Obon, presenting hanagasa dancers

- the ashibigami spirits of mountain and sea which visit communities in Yanbaru and nearby islands

- the boze of Akuseki Island (in the Tokara Islands) - enacted by villagers in large masks and grass skirts wielding long muddied staffs, who bring an energetic finale to each year's Obon

- the fusamara of Hateruma Island, who are covered in leaves and wear large cartoonish masks made from gourds, and who parade through the town praying for rain.

- the mayunganashi of Ishigaki Island, dressed in sedge hats and straw coats, who wield rokushakubô staffs and go around to each house bringing fortune for the new year

- the pantu of Miyako Island, figures covered in mud who visit each home and drive away evil or bad luck

- ancestral uyagan spirits welcomed in the Miyako Islands

References

- ↑ Aike Rots, "Strangers in the Sacred Grove: The Changing Meanings of Okinawan Utaki," Religions 10:298 (2019), 8.

- ↑ Rots, 8-9.

- ↑ The term used for "Heaven" or "Heavenly Beings" here is 天人, which in certain contexts could also refer to the Chinese people, or the Chinese emperor. See, for example, the Tenshikan, a hall for hosting envoys from the Chinese emperor, or, literally "Heavenly envoys." Such an interpretation would also align with the Sinocentric notion of the Chinese emperor as the source from whom civilized culture emanates.

- ↑ Yokoyama Manabu 横山学, Ryûkyû koku shisetsu torai no kenkyû 琉球国使節渡来の研究, Tokyo: Yoshikawa kôbunkan (1987), 52-53.

- ↑ "Nirai kanai," Okinawa Compact Encyclopedia 沖縄コンパクト事典, Ryukyu Shimpo, 1 March 2003.; Videos and exhibit displays, "Minzoku" (Folk Customs) exhibit, National Museum of Japanese History, Sakura, Chiba. Viewed July 2013.

- ↑ Gallery labels, "Ashage," Amami Nature and Culture Center, Amami Ôshima.[1]

- ↑ Gallery labels, "Kamimichi," Amami Nature and Culture Center, Amami Ôshima.[2]

- ↑ Gallery labels, "Unarigami," Amami Nature and Culture Center, Amami Ôshima.[3]

- ↑ George Kerr, Okinawa: the History of an Island People, Revised ed., Tuttle Publishing (2000), 111.

- ↑ Plaque on-site at former site of Kikoe-ôgimi udun, just outside Shuri Middle School, at 2-55 Tera-chô, Shuri, Naha.[4]; Plaques at reproduction of a noro's house, Okinawa Furusato Mura, Ocean Expo Park, Nakijin.[5].

- ↑ "Hinokami." Okinawa Compact Encyclopedia 沖縄コンパクト事典. Ryukyu Shimpo, 1 March 2003.; Gregory Smits. Visions of Ryukyu: Identity and Ideology in Early-Modern Thought and Politics. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1999. p165.

- ↑ Gallery labels, Okinawa Prefectural Museum.