Difference between revisions of "Prussian blue"

(Created page with "[[Image:神奈川沖浪裏.jpg|right|thumb|300px|''Under the Wave at Kanagawa'', one of the most famous images in all of Japanese art; it makes extensive use of Prussian blue....") |

|||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

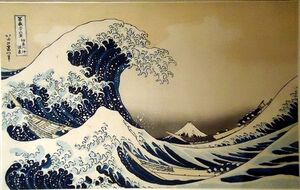

| − | [[ | + | [[File:Kanagawa-wave.jpg|right|thumb|300px|''Under the Wave at Kanagawa'', one of the most famous images in all of Japanese art; it makes extensive use of Prussian blue."]] |

Prussian blue, also known as Berlin blue, is considered the world's first artificial (chemical) pigment; that is to say, it is a paint or printing ink not made directly from plant, mineral, or other natural materials. The pigment is used in some of the most iconic and famous ''[[ukiyo-e]]'' woodblock prints, including the "Great Wave Off Kanagawa" and many others by [[Hokusai]] and [[Hiroshige]]. Prussian blue was highly prized in Japan as a blue pigment which, unlike [[dayflower blue]] and many other vegetable pigments, did not fade or discolor when exposed to light or moisture. | Prussian blue, also known as Berlin blue, is considered the world's first artificial (chemical) pigment; that is to say, it is a paint or printing ink not made directly from plant, mineral, or other natural materials. The pigment is used in some of the most iconic and famous ''[[ukiyo-e]]'' woodblock prints, including the "Great Wave Off Kanagawa" and many others by [[Hokusai]] and [[Hiroshige]]. Prussian blue was highly prized in Japan as a blue pigment which, unlike [[dayflower blue]] and many other vegetable pigments, did not fade or discolor when exposed to light or moisture. | ||

| − | + | ==History== | |

| + | The pigment was first invented by Johann Konrad Dippel and Johann Jacob Diesbach in the laboratory they shared in Berlin, sometime between [[1704]] and [[1707]]. Diesbach, a color-maker who was trying to synthesize a red dye from [[cochineal]], borrowed [[potash]] which Dippel had been using to extract oils from animal blood, and through some fortuitous accident in the process, the iron in the animal blood reacted with the potash and other materials in such a way that it created a blue substance which the two determined could function well as a dye or pigment. They began marketing their "Prussian blue" or "Berlin blue" soon afterwards, but kept the formula a secret until the Englishman John Woodward published a description of the procedure for producing it in the ''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society'' in [[1724]].<ref name=chen101>Buyun Chen, "The Craft of Color and the Chemistry of Dyes: Textile Technology in the Ryukyu Kingdom, 1700–1900," ''Technology and Culture'' 63:1 (January 2022), 101-102.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | For much of the first half of the 18th century, European chemists, dyers, and the like struggled to figure out how to make the substance easier to mass produce, and how to make it more effective in dyeing certain materials, such as cotton. French chemist Pierre-Joseph Macquer made one significant advance in [[1749]] when he discovered that using [[alum]] to mordant the cotton - weakening it slightly to make it less resistant to dyestuffs - was a successful technique.<ref name=chen101/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Perhaps the earliest use of Prussian blue in the (greater) Japanese archipelago is evident in a series of maps known as ''[[magiri-zu]]'' produced in the [[Ryukyu Kingdom|Ryûkyû Kingdom]] in [[1737]] to [[1750]].<ref>Gallery labels, ''Ryukyu/Okinawa no chizu ten'', Okinawa Prefectural Museum, Feb 2017.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | By [[1775]], Prussian blue, known in Chinese as ''yángqīng'' 洋青 or ''yángdiàn'' 洋靛, was among the goods being imported into the [[Qing Empire]] by English merchants. By [[1777]], [[Ryukyuan tributary missions to China|Ryukyuan tributary missions]] returning from China were bringing the pigment into Ryûkyû. | ||

Prussian blue was not widely used in mainland Japan until the 1830s, however, with a series of fan prints by [[Keisai Eisen]] from [[1829]] being perhaps the first to be printed entirely in Prussian blue (as ''[[ai-e]]'', or "blue pictures") without any other colors.<ref>"[http://shunga.honolulumuseum.org/2013/index.php?page=125&language=&maxImageHeight=470&headerTop=0&headerHeight=109&footerTop=579&bw=1366&sh=0&refreshed=refreshed#.VH1YvsmTLqM Tongue in Cheek: Erotic Art in 19th-Century Japan]," Honolulu Museum of Art, exhibition website, accessed 1 Dec 2014.</ref> Many of the most famous ''ukiyo-e'' images employing Prussian blue - such as Hokusai's "Great Wave," are from the 1830s. | Prussian blue was not widely used in mainland Japan until the 1830s, however, with a series of fan prints by [[Keisai Eisen]] from [[1829]] being perhaps the first to be printed entirely in Prussian blue (as ''[[ai-e]]'', or "blue pictures") without any other colors.<ref>"[http://shunga.honolulumuseum.org/2013/index.php?page=125&language=&maxImageHeight=470&headerTop=0&headerHeight=109&footerTop=579&bw=1366&sh=0&refreshed=refreshed#.VH1YvsmTLqM Tongue in Cheek: Erotic Art in 19th-Century Japan]," Honolulu Museum of Art, exhibition website, accessed 1 Dec 2014.</ref> Many of the most famous ''ukiyo-e'' images employing Prussian blue - such as Hokusai's "Great Wave," are from the 1830s. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Later in the 19th century, Prussian blue came to be used as an artificial additive in green [[tea]] exported to the United States, in order to deepen the color of the tea.<ref>Robert Hellyer, "1874: Tea and Japan's New Trading Regime," ''Asia Inside/Out: Changing Times'', Harvard University Press (2015), 190.</ref> | ||

{{stub}} | {{stub}} | ||

Latest revision as of 02:13, 24 July 2022

Prussian blue, also known as Berlin blue, is considered the world's first artificial (chemical) pigment; that is to say, it is a paint or printing ink not made directly from plant, mineral, or other natural materials. The pigment is used in some of the most iconic and famous ukiyo-e woodblock prints, including the "Great Wave Off Kanagawa" and many others by Hokusai and Hiroshige. Prussian blue was highly prized in Japan as a blue pigment which, unlike dayflower blue and many other vegetable pigments, did not fade or discolor when exposed to light or moisture.

History

The pigment was first invented by Johann Konrad Dippel and Johann Jacob Diesbach in the laboratory they shared in Berlin, sometime between 1704 and 1707. Diesbach, a color-maker who was trying to synthesize a red dye from cochineal, borrowed potash which Dippel had been using to extract oils from animal blood, and through some fortuitous accident in the process, the iron in the animal blood reacted with the potash and other materials in such a way that it created a blue substance which the two determined could function well as a dye or pigment. They began marketing their "Prussian blue" or "Berlin blue" soon afterwards, but kept the formula a secret until the Englishman John Woodward published a description of the procedure for producing it in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1724.[1]

For much of the first half of the 18th century, European chemists, dyers, and the like struggled to figure out how to make the substance easier to mass produce, and how to make it more effective in dyeing certain materials, such as cotton. French chemist Pierre-Joseph Macquer made one significant advance in 1749 when he discovered that using alum to mordant the cotton - weakening it slightly to make it less resistant to dyestuffs - was a successful technique.[1]

Perhaps the earliest use of Prussian blue in the (greater) Japanese archipelago is evident in a series of maps known as magiri-zu produced in the Ryûkyû Kingdom in 1737 to 1750.[2]

By 1775, Prussian blue, known in Chinese as yángqīng 洋青 or yángdiàn 洋靛, was among the goods being imported into the Qing Empire by English merchants. By 1777, Ryukyuan tributary missions returning from China were bringing the pigment into Ryûkyû.

Prussian blue was not widely used in mainland Japan until the 1830s, however, with a series of fan prints by Keisai Eisen from 1829 being perhaps the first to be printed entirely in Prussian blue (as ai-e, or "blue pictures") without any other colors.[3] Many of the most famous ukiyo-e images employing Prussian blue - such as Hokusai's "Great Wave," are from the 1830s.

Later in the 19th century, Prussian blue came to be used as an artificial additive in green tea exported to the United States, in order to deepen the color of the tea.[4]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Buyun Chen, "The Craft of Color and the Chemistry of Dyes: Textile Technology in the Ryukyu Kingdom, 1700–1900," Technology and Culture 63:1 (January 2022), 101-102.

- ↑ Gallery labels, Ryukyu/Okinawa no chizu ten, Okinawa Prefectural Museum, Feb 2017.

- ↑ "Tongue in Cheek: Erotic Art in 19th-Century Japan," Honolulu Museum of Art, exhibition website, accessed 1 Dec 2014.

- ↑ Robert Hellyer, "1874: Tea and Japan's New Trading Regime," Asia Inside/Out: Changing Times, Harvard University Press (2015), 190.