Suzuki Harunobu

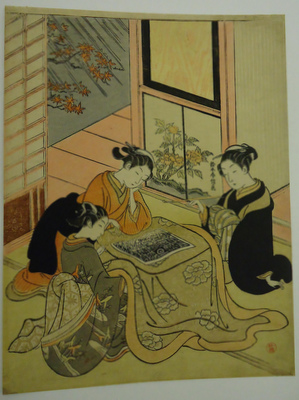

Suzuki Harunobu is one of the most famous and influential ukiyo-e artists. He is known chiefly as the inventor of the process for making full-color prints, which came to be called nishiki-e, and for his quite distinctive, and influential, style of portraying beautiful youths.

It is unclear who Harunobu may have studied under, though his style shows the strong influence of Nishimura Shigenaga and Nishikawa Sukenobu. He may have also had formal training under a Kanô school master. His early work, done in the late 1750s to early 1760s, reflects in particular the influence of the Torii school of ukiyo-e artists, who dominated the yakusha-e and bijinga modes.

Though Harunobu's nishiki-e would prove an exceptionally important development in the history of ukiyo-e, they derived originally from an obscure corner of the world of prints and popular culture. E-goyomi, or "calendar prints," did not explicitly display the months and days as a regular calendar would, but were single-sheet images which incorporated into their designs representations of which months in a given year would be the short months.

Harunobu was commissioned, beginning in 1765, by a poetry & prints appreciation circle headed by hatamoto Ôkubo Jinshirô, also known as Kyosen[1], to design such calendar prints for them. Unlike the cheap prints produced for the mass market, these commissioned calendar prints were created for a much smaller, and wealthier, audience, and so Harunobu was free to use far more expensive materials and methods. Catalpa wood was replaced with cherry wood for the woodblocks themselves, and more expensive colored inks were used. Harunobu also took advantage of the expanded budget to design prints with a greater number of colors, a process which required a greater number of blocks. The calendar prints he produced in 1765 and 1766 used better paper, thicker, more opaque colors, and would be reproduced for the mass market, marking a major shift in the way ukiyo-e prints were made, their quality, style, and appearance.

One of Harunobu's other great innovations, enabled by the advent of the full-color print, was the use of colored backgrounds. While some other artists had previously included some color in the backgrounds of their prints, most used either totally blank backgrounds, or some limited description of an actual setting. Harunobu was among the first to fill backgrounds with solid color, and the first to fill a background with black, or a dark color, to represent night; night scenes had previously been, and would continue to be in the vast majority of works, denoted simply by the presence of the moon, lanterns, candles, and the like, without any darkened background.

Harunobu died in 1770, only five years after introducing the nishiki-e print. However, in those last few years of his life, he produced over one thousand print designs, chiefly depictions of willowy young girls, and also a fair percentage of shunga (erotic prints), as most ukiyo-e artists did. He is known to have produced at least seven shunga volumes, alongside numerous single-sheet prints.[2] He also produced a number of paintings, and pioneered the reintroduction of larger print sizes, the chûban size having dominated for a time.

Though Harunobu was hardly the only artist to depict scenes from everyday life - as opposed to those from the kabuki theatre and pleasure quarters, fantasies removed from everyday life - ukiyo-e expert Richard Lane identifies him as influential in establishing and embracing the mode of depicting beauties from everyday life. A young girl by the name of Kasamori Osen appears in a great many of Harunobu's prints; not a courtesan herself, but merely a waitress, she epitomized for Harunobu the beauty that can be found in everyday life, outside of the pleasure quarters.

Lane summarizes Harunobu's vision as "idealistic but always focused on reality - the real as it should be but seldom is." Though Harunobu did produce quite a number of prints depicting courtesans and kabuki actors, his real focus was on the beauty to be found outside of those realms of fantasy, in the real world of everyday life.

He died in his 40s, at the peak of his career, leaving several disciples, including Harushige, who emulated the master's style so well that he passed off a number of his works as Harunobu's for years after the master's death. Though Harunobu's style and other innovations would prove quite influential, he did not have many followers or a direct school, and very few directly continued his style.

References

- Lane, Richard. Images from the Floating World. New York: Konecky & Konecky, 1978. pp99-111.

- Mason, Penelope. History of Japanese Art. Second Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2005. p283.

- ↑ Tanabe, Masako. "The Enigma of Elegance - Colorants and Paper in the Woodblock Prints of Suzuki Harunobu." in Seishun no ukiyo-eshi Suzuki Harunobu - Edo no kararisuto tôjô. Chiba City Museum of Art, 2002. p307.

- ↑ "The Arts of the Bedchamber: Japanese Shunga." Exhibition Website. Honolulu Museum of Art, 2012.