Difference between revisions of "Buddhist sculpture in Korea"

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

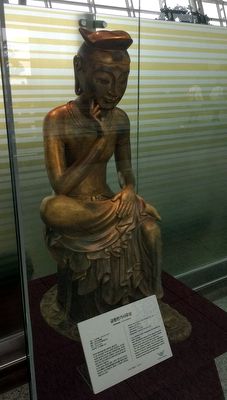

| + | [[File:Maitreya83.jpg|right|thumb|400px|Replica on display at Incheon Airport of [[National Treasure of Korea]] #83, a gilt-bronze Maitreya sculpture very closely related in style to the 7th century [[Koryu-ji|Kôryû-ji]] sculpture which was the first to be designated a [[National Treasure]] in Japan]] | ||

Buddhism is believed to have been introduced into the Korean kingdoms of [[Koguryo]] and [[Paekche]] in the 4th century, via the [[Northern Wei Dynasty]] ([[386]]-[[534]]), a dynasty of the [[Tuoba]] people, a Turkic people descended from the [[Xianbei]].<ref name=rawski123>Evelyn Rawski, ''Early Modern China and Northeast Asia: Cross-Border Perspectives'', Cambridge University Press (2015), 123-125.</ref> Though Korea initially copied Chinese styles of Buddhist sculpture, distinctive styles later emerged in each of the [[Three Kingdoms (Korea)|Three Kingdoms]]. These styles then merged into a single set of typical styles following the unification of Korea under the kingdom of [[Silla]] in the 7th century. | Buddhism is believed to have been introduced into the Korean kingdoms of [[Koguryo]] and [[Paekche]] in the 4th century, via the [[Northern Wei Dynasty]] ([[386]]-[[534]]), a dynasty of the [[Tuoba]] people, a Turkic people descended from the [[Xianbei]].<ref name=rawski123>Evelyn Rawski, ''Early Modern China and Northeast Asia: Cross-Border Perspectives'', Cambridge University Press (2015), 123-125.</ref> Though Korea initially copied Chinese styles of Buddhist sculpture, distinctive styles later emerged in each of the [[Three Kingdoms (Korea)|Three Kingdoms]]. These styles then merged into a single set of typical styles following the unification of Korea under the kingdom of [[Silla]] in the 7th century. | ||

| − | [[Tang Dynasty]] sculptural styles had a notable influence in the 7th-8th centuries, and Korean Buddhist sculpture developed into a "mature classical style" in the 8th century, a period sometimes described as a "golden age" for Korean Buddhist art. | + | [[Tang Dynasty]] sculptural styles had a notable influence in the 7th-8th centuries, and Korean Buddhist sculpture developed into a "mature classical style" in the 8th century, a period sometimes described as a "golden age" for Korean Buddhist art. Meanwhile, the supply of [[copper]] dwindled, and the construction of Buddhist sculpture in [[iron]] - not widely used in Chinese or Japanese sculpture at all - flourished. |

Chinese influences faded beginning in the 9th century, and the 10th to 12th centuries saw considerable growth and development in native Korean styles, including the production of a number of colossal Buddhist images. Buddhism and Buddhist sculpture flourished in the [[Goryeo]] Kingdom ([[918]]-[[1392]]), and came to be influenced by Tibeto-Mongolian styles in the 13th-14th centuries as the [[Mongols|Mongol]] [[Yuan Dynasty]] rose to dominance in China. | Chinese influences faded beginning in the 9th century, and the 10th to 12th centuries saw considerable growth and development in native Korean styles, including the production of a number of colossal Buddhist images. Buddhism and Buddhist sculpture flourished in the [[Goryeo]] Kingdom ([[918]]-[[1392]]), and came to be influenced by Tibeto-Mongolian styles in the 13th-14th centuries as the [[Mongols|Mongol]] [[Yuan Dynasty]] rose to dominance in China. | ||

| Line 9: | Line 10: | ||

{{stub}} | {{stub}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==See also== | ||

| + | *[[Buddhist sculpture]] | ||

| + | *[[Buddhist sculpture in China]] | ||

| + | *[[Buddhist sculpture in Ryukyu]] | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *Gallery labels, National Museum of Korea.[https://www.flickr.com/photos/toranosuke/48312383256/sizes/l] | + | *Gallery labels, National Museum of Korea.[https://www.flickr.com/photos/toranosuke/48312383256/sizes/l][https://www.flickr.com/photos/toranosuke/48312405591/in/photostream/] |

<references/> | <references/> | ||

[[Category:Buddhism]] | [[Category:Buddhism]] | ||

[[Category:Art and Architecture]] | [[Category:Art and Architecture]] | ||

Latest revision as of 09:00, 11 August 2019

Buddhism is believed to have been introduced into the Korean kingdoms of Koguryo and Paekche in the 4th century, via the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534), a dynasty of the Tuoba people, a Turkic people descended from the Xianbei.[1] Though Korea initially copied Chinese styles of Buddhist sculpture, distinctive styles later emerged in each of the Three Kingdoms. These styles then merged into a single set of typical styles following the unification of Korea under the kingdom of Silla in the 7th century.

Tang Dynasty sculptural styles had a notable influence in the 7th-8th centuries, and Korean Buddhist sculpture developed into a "mature classical style" in the 8th century, a period sometimes described as a "golden age" for Korean Buddhist art. Meanwhile, the supply of copper dwindled, and the construction of Buddhist sculpture in iron - not widely used in Chinese or Japanese sculpture at all - flourished.

Chinese influences faded beginning in the 9th century, and the 10th to 12th centuries saw considerable growth and development in native Korean styles, including the production of a number of colossal Buddhist images. Buddhism and Buddhist sculpture flourished in the Goryeo Kingdom (918-1392), and came to be influenced by Tibeto-Mongolian styles in the 13th-14th centuries as the Mongol Yuan Dynasty rose to dominance in China.

The adoption of neo-Confucianism as the official political philosophy of state under the Joseon dynasty (1392-1897) brought some considerable suppression of Buddhism; however, images continued to be constructed and worshipped throughout that period, down to today.

See also

References

- ↑ Evelyn Rawski, Early Modern China and Northeast Asia: Cross-Border Perspectives, Cambridge University Press (2015), 123-125.