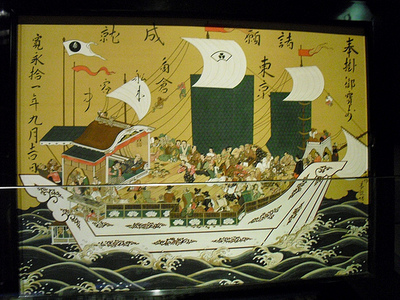

- Japanese: 朱印船 (shuinsen)

In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, merchants trading in Southeast Asia carried official permits, marking them as licensed traders and differentiating them from smugglers and pirates. These permits were stamped with a red seal (shuin), and as a result, the traders' ships came to be known as shuinsen, or "red seal ships."

The system was begun by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, but was further systematized under Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu, who appointed a bugyô (magistrate) to Nagasaki, and planned a system of governing foreign trade. He sought to guarantee (maintain) revenue from foreign trade while enforcing the ban on Christianity, and granted red seal licenses to daimyô and merchants who sought to engage in overseas trade. Daimyô were no longer permitted to hold red seal licenses, however, after 1612, as part of efforts to strengthen the security of Tokugawa rule by restricting daimyô power. Further, while red seal licenses continued to be issued to non-Japanese ship captains, patrons, or merchants, ship crews were required to include at least a certain proportion of Japanese crew members.[1]

Many of the ships were constructed according to a fusion of European and East Asian forms, e.g. combining European rigging with an East Asian junk's hull. Portuguese piloted many of these ships, and there are numerous records of European sailors coming across red seal ships and describing them as possessing a decidedly strange appearance, because of their mixed crews and mixed construction. Most were built in Nagasaki, though some red seal merchants commissioned ships from Chinese shipwrights in Ayutthaya. These East Asian or hybrid ships generally carried about 200-250 people, and 500-750 tons of cargo, in contrast to Iberian ships of the time, which were larger, carrying about 1000 tons.[2]

Red seal ships traveled to a number of ports in Southeast Asia; in 1624, for example, 35 ships traveled to Siam, 26 to Vietnam, two to Brunei, 30 to the Philippines, 23 to Cambodia, and one to Melaka.[3] Due to the patterns of seasonal winds, ships generally left Japan for Southeast Asia in mid-winter, and returned in early summer. The journey took on average about 47 days.[4]

In the time of the third Tokugawa shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu, the system was strengthened, adding the requirement of obtaining a hôsho, a second license or permission, from the rôjû (the chief shogunate elders), and addressed to the Nagasaki bugyô, granting the merchant permission to depart. This came after the realization by the shogunate that many of the shuinjô licenses given to foreign merchants were being used by daimyô or other high-ranking shogunate officials to engage in illegal trade; thus, the system had to be strengthened.[5]

Among the merchants who were granted red seal licenses and permission to engage in overseas trade, there were those who came to be known as the seven Great Red Seal Ship Families, who the shogunate remembered and appreciated. In Kyoto, these families included the Sueyoshi and Fushimi families, the house of Chaya Shirôjirô, and the house of Suminokura Ryôi. The son of William Adams also continued to enjoy "red seal" trading privileges, adopting his father's sobriquet, Miura Anjin.[5] Merchants frequently made offerings of ema (votive tablets) at Kiyomizu-dera before departing for Southeast Asia, in order to pray for a safe journey. Unlike the ema sold today at Shinto shrines, which are about the size of a postcard (though a good half-inch thick), these ema could be as large as several meters on a side.

The shuinsen (red seal ships) system ended, however, with the implementation of maritime restrictions in the 1630s-1640. By that time, roughly 350 licenses had been issued, including 43 to Chinese merchants and 38 to Europeans,[5] though for at least part of this period it was required that license-holders had to have at least partially Japanese crews.[6]

References

- Gallery labels at Museum of Kyoto.

- ↑ William Wray, “The Seventeenth-century Japanese Diaspora: Questions of Boundary and Policy,” in Ina Baghdiantz McCabe et al (eds.), Diaspora Entrepreneurial Networks, Oxford: Berg (2005), 82.

- ↑ Cesare Polenghi, Samurai of Ayutthaya: Yamada Nagamasa, Japanese warrior and merchant in early seventeenth-century Siam. Bangkok: White Lotus Press (2009), 18-19.

- ↑ Geoffrey Gunn, History Without Borders: The Making of an Asian World Region, 1000-1800, Hong Kong University Press (2011), 215-216.

- ↑ Polenghi, 19.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Marius Jansen, China in the Tokugawa World, Harvard University Press (1992), 18-19.

- ↑ Kang, David C. “Hierarchy in Asian International Relations: 1300-1900.” Asian Security 1, no. 1 (2005), 69.

External Links

- Examples of red seal licenses to Luzon (Philippines) and Cochinchina (central/southern Vietnam), from a copy of the Gaiban Shokan (1818), National Archives of Japan.