Ryukyuan pottery

- Okinawan: 焼物 (yachimun)

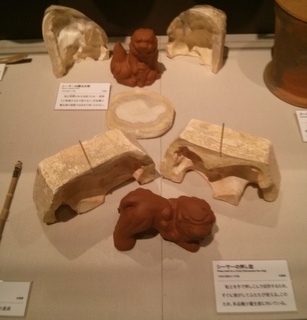

Pottery was first introduced to Ryûkyû from China during the Gusuku Period (c. 1100s-1400s). Tsuboya wares, produced in the Tsuboya district of Naha, are the most well-known style of Ryukyuan pottery, and the most strongly associated with Ryûkyû. In addition to dishes, vessels, and roof tiles, Ryukyuan pottery is especially known for the production of funerary urns, and shisa, lion-like guardians placed on rooftops and at gates to protect homes and other spaces from evil spirits.

History

In the early 17th century, Wakuta was the chief center of ceramics production on Okinawa, with Kogachi and Chibana developing shortly afterwards. In 1682, however, the court ordered many of the potters in the kingdom to relocate to the Tsuboya district, which was not until then a kiln site. This, then, constituted the creation of Tsuboya as a major center of pottery production, and sparked the emergence of a distinctive Tsuboya style, as potters from across the kingdom combined their techniques and styles. Kumejima, Miyakojima, and Ishigakijima remained major centers of pottery production as well, however, at this time.

Up until the Meiji period, Tsuboya remained a center of production of relatively simple arayachi (荒焼, "rough wares"), or unglazed ceramics. Jôyachi (上焼, "completed wares"), or glazed ceramics, were produced elsewhere in Ryûkyû, however, since at least the early 17th century, using techniques introduced by potters from Satsuma (including Korean potters abducted by Satsuma forces during the Imjin War in the 1590s). Additional styles and techniques continued to be introduced from both Satsuma and China in later eras.<[1] Still, it was only in the Taishô period that, seeing the great popularity of Arita wares in the mainland Japanese market and seeking to expand their market share, the Tsuboya potters began producing jôyachi with the elaborate designs of fish, dragons, and the like now so strongly associated with the district (and with Ryûkyû more broadly).

Tsuboya led Ryukyuan pottery through the 1960s, but in the 1970s, environmental and other concerns inspired many potters to relocate from Tsuboya - in the center of the city of Naha - to other areas, including Yomitan and Ôgimi-son, where they built new kilns in the traditional manner. A number of kilns are still active in Tsuboya, however, while other Tsuboya kilns are today maintained as cultural/historical sites. The Aragaki house and its associated agari-nu-kama ("eastern kiln") have been designated a National Important Cultural Property, while the fee-nu-kama ("southern kiln"), the only remaining arayachi (unglazed wares) kiln in the neighborhood, has been designated an Important Cultural Property by the prefecture. Both feature nobori gama climbing kilns; the agari-nu-kama is roughly 23 meters long by 4 meters wide, while the fee-nu-kama is roughly 20 meters long, and eight meters wide. The latter produced chiefly jugs for water and awamori, and ceramic funerary containers, and is known for the relatively intact state of its stonework construction.[2]

References

- Gallery labels, Okinawa Prefectural Museum.

- Gallery labels, "The Tsuboya-yaki region" and "Okinawan pottery," Gallery 4: Minzoku, National Museum of Japanese History.