Difference between revisions of "Hokusai"

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

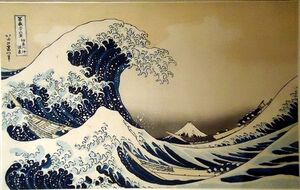

| − | [[ | + | [[File:Kanagawa-wave.jpg|right|thumb|300px|Hokusai's most famous work, ''Under the Wave at Kanagawa'', from his series "[[36 Views of Mt. Fuji]]."]] |

*''Born: [[1760]]/9'' | *''Born: [[1760]]/9'' | ||

*''Died: [[1849]]/4/18'' | *''Died: [[1849]]/4/18'' | ||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

Hokusai left the Katsukawa school in [[1793]], at the age of 33, expelled according to some accounts. This came shortly after the death of both his master Katsukawa Shunshô, and his own young wife, who left him with a son and two daughters, Omiyo and Otetsu.<ref name=davis>Kobayashi Tadashi and Julie Nelson Davis. "The Floating World in Light and Shadow: Ukiyo-e Paintings by Hokusai's Daughter Oi." in Carpenter, John et al (eds). ''Hokusai and his Age''. Hotei Publishing, 2005. pp93-103.</ref> Extremely little is known of their biographies, but Omiyo is known to have married book illustrator [[Yanagawa Shigenobu]], who Hokusai then later adopted as his own son. | Hokusai left the Katsukawa school in [[1793]], at the age of 33, expelled according to some accounts. This came shortly after the death of both his master Katsukawa Shunshô, and his own young wife, who left him with a son and two daughters, Omiyo and Otetsu.<ref name=davis>Kobayashi Tadashi and Julie Nelson Davis. "The Floating World in Light and Shadow: Ukiyo-e Paintings by Hokusai's Daughter Oi." in Carpenter, John et al (eds). ''Hokusai and his Age''. Hotei Publishing, 2005. pp93-103.</ref> Extremely little is known of their biographies, but Omiyo is known to have married book illustrator [[Yanagawa Shigenobu]], who Hokusai then later adopted as his own son. | ||

| − | Taking the name Sôri, Hokusai continued to produce works in his own personal style, in a variety of formats (single sheets, books, ''surimono'', etc.) and themes. It is said that his "strikingly individual style [of depictions of] frail, wistful female figure[s]"<ref>Lane. ''Images from the Floating World''. p162.</ref> emerged at this time, and would have cemented his legacy as a first-rate figure artist, had he not gone on to do so much more over the course of his nearly 90 years of life. | + | Taking the name Sôri, Hokusai continued to produce works in his own personal style, in a variety of formats (single sheets, books, ''surimono'', etc.) and themes. It is said that his "strikingly individual style [of depictions of] frail, wistful female figure[s]"<ref>Lane. ''Images from the Floating World''. p162.</ref> emerged at this time, and would have cemented his legacy as a first-rate figure artist, had he not gone on to do so much more over the course of his nearly 90 years of life. Many of these works were designed for small print runs for small private poetry circles, but some were later republished more widely. In the early decades of his career, from the 1780s into the 1800s, he produced book illustrations chiefly for ''[[kibyoshi|kibyôshi]]'', but early in the 1800s, he shifted away from ''kibyôshi'' to ''[[yomihon]]'' - larger books, with full-page illustrations interspersed with pages of text. His first venture into illustrations of Chinese subjects was ''Shinpen Suikogaden'', an illustrated book version of ''[[Suikoden]]'' published serially from [[1805]] into the 1830s. This set was one of a number of publications in which he was given equal billing with the writer, a sign of the power of his name for selling books.<ref name=tinios-ucsb/> |

In [[1797]], he first took the name "Hokusai." Devoid of the patronage or support network of a school, for a time he peddled his works alongside condiments and calendars in order to make a living. He continued to produce works in a wide variety of themes and formats, and by the early 1800s was quite active in producing book illustrations to meet the demand of a trend at the time for Chinese subjects and Chinese-style images. [[Richard Lane]] comments that his extensive work with Chinese styles and historical themes in this period caused him to drift away from the aspects which made his figures so compelling or beautiful; they lost some of their softness and grace. However, Hokusai's work became much more dramatic in this period, and became stronger in its depictions of natural landscapes and architecture. | In [[1797]], he first took the name "Hokusai." Devoid of the patronage or support network of a school, for a time he peddled his works alongside condiments and calendars in order to make a living. He continued to produce works in a wide variety of themes and formats, and by the early 1800s was quite active in producing book illustrations to meet the demand of a trend at the time for Chinese subjects and Chinese-style images. [[Richard Lane]] comments that his extensive work with Chinese styles and historical themes in this period caused him to drift away from the aspects which made his figures so compelling or beautiful; they lost some of their softness and grace. However, Hokusai's work became much more dramatic in this period, and became stronger in its depictions of natural landscapes and architecture. | ||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

Hokusai's eldest son became the heir to the Nakajima family, earning the artist a stipend, and a considerable degree of financial security. He produced many works during this time which were given away as gifts, rather than charging commission or selling them on the street. His son died around 1812, however, and so Hokusai had to return to centering his production on meeting demand, and on seeking commissions. He began to produce picture books, including some aimed at helping younger artists practice and train, and began seeking out disciples. | Hokusai's eldest son became the heir to the Nakajima family, earning the artist a stipend, and a considerable degree of financial security. He produced many works during this time which were given away as gifts, rather than charging commission or selling them on the street. His son died around 1812, however, and so Hokusai had to return to centering his production on meeting demand, and on seeking commissions. He began to produce picture books, including some aimed at helping younger artists practice and train, and began seeking out disciples. | ||

| − | During this high point in his career, Hokusai made paintings as well, very expensive commissions as compared to print designs, including many with very lavish colors on gold-foil backgrounds. On a number of occasions he painted for an audience - on at least one occasion, for the shogun - and often painted especially large works, for the sake of display. | + | During this high point in his career, Hokusai made paintings as well, very expensive commissions as compared to print designs, including many with very lavish colors on gold-foil backgrounds. On a number of occasions he painted for an audience - on at least one occasion, for the shogun - and often painted especially large works, for the sake of display. He also designed numerous painting manuals beginning with ''Ryakuga haya oshie'' in [[1812]] - more Edo period painting manuals bear Hokusai's name than that of any other artist, though not all books bearing Hokusai's name were actually designed by him.<ref name=tinios-ucsb/> |

| − | In | + | In 1812, Hokusai traveled to [[Nagoya]] - one of his few journeys outside of Edo. There, he met the publisher [[Eirakuya Toshiro|Eirakuya Tôshirô]], who convinced him to prepare a series of sketchbooks, which amateur artists might use as guides. The resulting ''[[Hokusai Manga]]'' was published over many years, with some volumes coming out even after Hokusai's death; it remains an exceptionally popular publication today.<ref>Christine Guth, ''Art of Edo Japan'', Yale University Press (1996), 114.</ref> The ''manga'' was originally published as a standalone volume, and original copies are still labeled with ''zen'' (全, "complete") on the cover. Additional volumes were produced in response to its commercial success and popularity, with 12 volumes in total being designed directly by Hokusai, and another three being added even after his death, with the last one coming out in [[1878]].<ref name=tinios-ucsb/> |

| + | |||

| + | Hokusai designed numerous ''[[shunga|shunpon]]'' (erotic books) over the course of his career, up until [[1822]], when he shifted away from such works. The [[Utagawa school]] of artists would then become the dominant ''shunpon'' illustrators of the 1830s-1840s.<ref name=tinios-ucsb/> | ||

Hokusai's second wife died in [[1828]], when the artist was 68. She had given him another son, Sakijûrô, a daughter, [[Katsushika Oi|Ôi]] (also known as O-ei), and possibly another daughter, Onao. The rest of his family having either married and left home, or passed away, he had been living for a time in a rather difficult arrangement, with his wife, eldest daughter, who had divorced and returned home, and a delinquent grandson. Shortly after his wife's death, Hokusai's daughter and pupil Katsushika Ôi, an artist in her own right, divorced from her husband, and returned to her father's side, remaining with him the rest of his life. | Hokusai's second wife died in [[1828]], when the artist was 68. She had given him another son, Sakijûrô, a daughter, [[Katsushika Oi|Ôi]] (also known as O-ei), and possibly another daughter, Onao. The rest of his family having either married and left home, or passed away, he had been living for a time in a rather difficult arrangement, with his wife, eldest daughter, who had divorced and returned home, and a delinquent grandson. Shortly after his wife's death, Hokusai's daughter and pupil Katsushika Ôi, an artist in her own right, divorced from her husband, and returned to her father's side, remaining with him the rest of his life. | ||

| Line 44: | Line 46: | ||

Though he had produced many landscape works in earlier years, it was around 1830 that Hokusai began work on the "Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji", and entered a period of his career which would later come to define him as one of the greatest of all Japanese landscape artists. | Though he had produced many landscape works in earlier years, it was around 1830 that Hokusai began work on the "Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji", and entered a period of his career which would later come to define him as one of the greatest of all Japanese landscape artists. | ||

| − | [[Hiroshige]]'s "Fifty-three Stations of the [[Tokaido|Tôkaidô]]" was published in [[1833]], spurring Hokusai to create the three-volume | + | [[Hiroshige]]'s "Fifty-three Stations of the [[Tokaido|Tôkaidô]]" was published in [[1833]], spurring Hokusai to create the three-volume illustrated book "[[One Hundred Views of Fuji]]." |

It was in these last decades of his life that Hokusai produced a great many landscape series, including "Eight Views of Edo", "Eight Views of Ryukyu", "Oceans of Wisdom", and "Rare Views of Famous Japanese Bridges", while continuing to produce prints and paintings with a wide variety of themes and subjects. | It was in these last decades of his life that Hokusai produced a great many landscape series, including "Eight Views of Edo", "Eight Views of Ryukyu", "Oceans of Wisdom", and "Rare Views of Famous Japanese Bridges", while continuing to produce prints and paintings with a wide variety of themes and subjects. | ||

Latest revision as of 00:46, 24 July 2022

Katsushika Hokusai was an ukiyo-e painter and print designer, possibly the most famous figure in all of Japanese art history. In his own time, however, he was most famous and popular for his book illustrations.[1]

Though best known today for his series of single sheet woodblock print landscapes, in particular his "Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji," Hokusai was a quite prolific artist, producing woodblock print designs for single-sheets, illustrated books, picture books (ehon), and surimono, as well as paintings in formats ranging from byôbu and hanging scrolls to banners and paper lanterns[2]. Hokusai's books disseminated more widely than those illustrated by any other Japanese illustrator, and were kept in print longer. In Europe, too, Hokusai was known for his books long before there was any widespread awareness of his paintings or prints.[1] The subjects depicted in his works also run the gamut, from beautiful women, kabuki actors, and sumo wrestlers, to landscapes, to historical subjects, birds-and-flowers, ghost tales, and depictions of tigers, dragons, and phoenixes.

Over the course of his career, Hokusai took on many pseudonyms, and occupied many residences - mostly in eastern Edo. He was extremely prolific, painting over 30,000 designs, and while he loved to travel, is said to have truly devoted himself to his art, never smoking or drinking, and working on his art from early morning until late at night, for many of his years.

Early Life

Born in the Honjo neighborhood just east of Edo, young Tokitarô was adopted by the Nakajima family, artisans who produced mirrors for the shogunal family. He was never named heir to the family nor apprenticed in their trade, however.

It is believed that his original family name may have been Kawamura, as that name appears on his gravestone. There are theories that Hokusai was the true son of the head of the Nakajima family, but was born to a mistress or concubine, and that this is why he was not raised as heir; other theories suggest that Nakajima was his uncle, and that he was in fact not adopted until his late teens. He claimed his mother was of the samurai class, grand-daughter of a retainer to Kira Yoshinaka.

Hokusai would later write that he had a passion for drawing since the age of five, and he is known to have lost a sister at the age of six, though little else is known about his childhood. He is known to have worked as a clerk and delivery boy for a bookstore in his youth, during which time he was called Tetsuzô, and to have been apprenticed to a woodblock carver from the age of 15 to 18. In 1775, he carved his first blocks of text, a sharebon or light novel set in the Yoshiwara, though he, like all ukiyo-e artists, would never carve blocks for his own prints.

Early Career as an Artist

At the age of 18, in 1778, the young artist-to-be began studying under Katsukawa Shunshô, head of the Katsukawa school of ukiyo-e. Taking the art-name Shunrô, the young artist published his first prints - yakusha-e, or images of kabuki actors, a theme in which the Katsukawa school specialized - in the Eighth month of the following year.

Under the tutelage of Shunshô, Hokusai produced a number of prints of kabuki actors, sumo wrestlers, and beautiful women, as well as landscape uki-e prints which experimented with Western perspective, illustrated books, and surimono, more expensive, privately commissioned or purchased works, which were more lavishly made and were either unique or made in very low print runs.

He is believed to have married in his early 20s, and though he stayed with the Katsukawa school, the style and subject matter of his works drifted away from those of the school. He began to focus, in both single sheet prints and illustrated books, on historical subjects and landscapes, taking stylistic influence from Torii Kiyonaga, Kitao Shigemasa, and others. Throughout his early career, Hokusai studied a wide variety of styles, refusing to restrict himself to just one master, though the strictures of the school system expected that of him. In addition to studying secretly under the Kanô school master Kanô Yûsen, from whom he acquired an understanding and appreciation of brushwork and Chinese (-inspired) imagery and motifs, he also studied the ink paintings of Sesshû, the work of Ogata Kôrin and of several artists of the Tosa school, as well as what little he could of Western painting. He would also study under Shiba Kôkan, master of Japanese Western-style painting, in 1796, adopting and adapting all of these disparate influences into his own personal style.

As an Independent Artist

Hokusai left the Katsukawa school in 1793, at the age of 33, expelled according to some accounts. This came shortly after the death of both his master Katsukawa Shunshô, and his own young wife, who left him with a son and two daughters, Omiyo and Otetsu.[3] Extremely little is known of their biographies, but Omiyo is known to have married book illustrator Yanagawa Shigenobu, who Hokusai then later adopted as his own son.

Taking the name Sôri, Hokusai continued to produce works in his own personal style, in a variety of formats (single sheets, books, surimono, etc.) and themes. It is said that his "strikingly individual style [of depictions of] frail, wistful female figure[s]"[4] emerged at this time, and would have cemented his legacy as a first-rate figure artist, had he not gone on to do so much more over the course of his nearly 90 years of life. Many of these works were designed for small print runs for small private poetry circles, but some were later republished more widely. In the early decades of his career, from the 1780s into the 1800s, he produced book illustrations chiefly for kibyôshi, but early in the 1800s, he shifted away from kibyôshi to yomihon - larger books, with full-page illustrations interspersed with pages of text. His first venture into illustrations of Chinese subjects was Shinpen Suikogaden, an illustrated book version of Suikoden published serially from 1805 into the 1830s. This set was one of a number of publications in which he was given equal billing with the writer, a sign of the power of his name for selling books.[1]

In 1797, he first took the name "Hokusai." Devoid of the patronage or support network of a school, for a time he peddled his works alongside condiments and calendars in order to make a living. He continued to produce works in a wide variety of themes and formats, and by the early 1800s was quite active in producing book illustrations to meet the demand of a trend at the time for Chinese subjects and Chinese-style images. Richard Lane comments that his extensive work with Chinese styles and historical themes in this period caused him to drift away from the aspects which made his figures so compelling or beautiful; they lost some of their softness and grace. However, Hokusai's work became much more dramatic in this period, and became stronger in its depictions of natural landscapes and architecture.

Hokusai's eldest son became the heir to the Nakajima family, earning the artist a stipend, and a considerable degree of financial security. He produced many works during this time which were given away as gifts, rather than charging commission or selling them on the street. His son died around 1812, however, and so Hokusai had to return to centering his production on meeting demand, and on seeking commissions. He began to produce picture books, including some aimed at helping younger artists practice and train, and began seeking out disciples.

During this high point in his career, Hokusai made paintings as well, very expensive commissions as compared to print designs, including many with very lavish colors on gold-foil backgrounds. On a number of occasions he painted for an audience - on at least one occasion, for the shogun - and often painted especially large works, for the sake of display. He also designed numerous painting manuals beginning with Ryakuga haya oshie in 1812 - more Edo period painting manuals bear Hokusai's name than that of any other artist, though not all books bearing Hokusai's name were actually designed by him.[1]

In 1812, Hokusai traveled to Nagoya - one of his few journeys outside of Edo. There, he met the publisher Eirakuya Tôshirô, who convinced him to prepare a series of sketchbooks, which amateur artists might use as guides. The resulting Hokusai Manga was published over many years, with some volumes coming out even after Hokusai's death; it remains an exceptionally popular publication today.[5] The manga was originally published as a standalone volume, and original copies are still labeled with zen (全, "complete") on the cover. Additional volumes were produced in response to its commercial success and popularity, with 12 volumes in total being designed directly by Hokusai, and another three being added even after his death, with the last one coming out in 1878.[1]

Hokusai designed numerous shunpon (erotic books) over the course of his career, up until 1822, when he shifted away from such works. The Utagawa school of artists would then become the dominant shunpon illustrators of the 1830s-1840s.[1]

Hokusai's second wife died in 1828, when the artist was 68. She had given him another son, Sakijûrô, a daughter, Ôi (also known as O-ei), and possibly another daughter, Onao. The rest of his family having either married and left home, or passed away, he had been living for a time in a rather difficult arrangement, with his wife, eldest daughter, who had divorced and returned home, and a delinquent grandson. Shortly after his wife's death, Hokusai's daughter and pupil Katsushika Ôi, an artist in her own right, divorced from her husband, and returned to her father's side, remaining with him the rest of his life.

Later Career

Though he had produced many landscape works in earlier years, it was around 1830 that Hokusai began work on the "Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji", and entered a period of his career which would later come to define him as one of the greatest of all Japanese landscape artists.

Hiroshige's "Fifty-three Stations of the Tôkaidô" was published in 1833, spurring Hokusai to create the three-volume illustrated book "One Hundred Views of Fuji."

It was in these last decades of his life that Hokusai produced a great many landscape series, including "Eight Views of Edo", "Eight Views of Ryukyu", "Oceans of Wisdom", and "Rare Views of Famous Japanese Bridges", while continuing to produce prints and paintings with a wide variety of themes and subjects.

Hokusai died in 1849, at the age of 89. His death poem reads:

人魂で Even as a ghost

行く気散じや I'll gaily tread

夏野原 The summer moors[6]

It is said that his daughter Katsushika Ôi was the only person by his side when he died, and that his last words were "let me live just ten more years, just five more years..."[3]

References

- Lane, Richard. Hokusai: Life and Work. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1989.

- Lane, Richard. Images from the Floating World. New York: Konecky & Konecky, 1978. pp159-171; 255.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Ellis Tinios, "Hokusai: The Name that Sold Books," lecture, UC Santa Barbara, 24 April 2018.

- ↑ Examples of some of his paintings, including ones on more obscure formats, can be found in Nishimura Morse, Anne (ed.) Edo no yûwaku: The Allure of Edo: Ukiyo-e Painting from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun Company, 2006.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Kobayashi Tadashi and Julie Nelson Davis. "The Floating World in Light and Shadow: Ukiyo-e Paintings by Hokusai's Daughter Oi." in Carpenter, John et al (eds). Hokusai and his Age. Hotei Publishing, 2005. pp93-103.

- ↑ Lane. Images from the Floating World. p162.

- ↑ Christine Guth, Art of Edo Japan, Yale University Press (1996), 114.

- ↑ Translation from Lane. Images from the Floating World. p169.