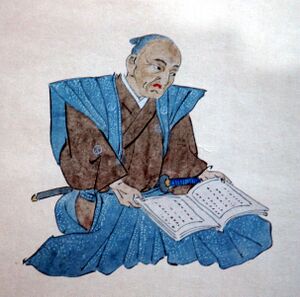

Kumazawa Banzan

The storied warrior-philosopher of the Edo Period. He was the most able pupil of Nakae Tôju 中江藤樹, the founder of the Yang-ming (Yômei陽明) school of philosophy in Japan. This "school of the mind" applied the introspectiveness of the school of mind to political theory in Japan following the Edo Period. This school seen as one in which the human mind is an embodying the principle of the universe, as opposed to the "school of principle".

Kumazawa's family was a ronin family, but at fifteen years of age he was able to take a position under Ikeda Mitsumasa, lord of Okayama in Bizen province. According to his own writing, he drilled dilligently in the martial arts with special zeal, determined to become a worthy samurai. He gave up eating rice so as not to take on weight, and refrained from contact with women for ten years. When he was stationed as a guard in the Ideda mansion at Edo he would practice in swordsmanship at night with a wooden sword (bokken). In order to maintain good physical condition he would run on rooftops of the outbuildings of the mansion, surprising those colleagues who noticed him and making them think he was possessed.

He left Ikeda's service to study with Nakae, but re-entered it in 1647 and became chief minister and launched a spectacularly successful reform program. However, he made enemies among conservatives and was forced to resign in 1656, and was harassed sometimes after that. In 1687 he submitted a program of reform to the shogun, but it caused such a furor he was kept in custody or surveillance until he died.

Kumazawa Banzan served in a high administrative post and was assigned to study philosophical and economic problems in regards to samurai life. He condemned meaningless waste of rice and talent along with idleness among the samurai class. Banzan's goal was to reform the Japanese government by advocating the adoption of a political system based on merit rather than heredity and the employment of political principles to fit the situation. The Tokugawa regime in the end responded quite poorly to this idea, due to the fact that the shogunate was fixed in the hereditary ways.

References

- Tsunoda, Ryusaku, et. al., comp., Sources of Japanese Tradition, Columbia University Press, 1958.