Hanaogi

- Japanese: 花扇 (hanaougi)

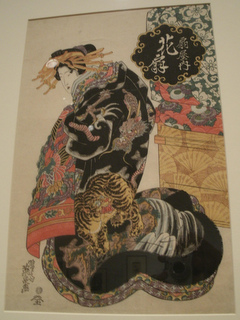

Hanaôgi was the name of a series of prominent courtesans of the Yoshiwara's Ôgiya teahouse. Little is known about any of the individuals to be known by this myôseki[1], nor about the precise chronology of their retirement and succession.

Hanaôgi II, who flourished in the 1770s, was known for her especially great talent at poetry, koto, tea ceremony, and calligraphy, among other arts; her successor Hanaôgi III was celebrated for the same. They enjoyed a very high status within the Yoshiwara, and Hanaôgi II in particular had as many as eight shinzô attendants - considerably more than most courtesans. Throughout the period, shinzô in the service to Hanaôgi took names featuring the character hana, such as Hanasumi, Hanazono, Hanatsuru, and Hanakishi.[2]

An anecdote about Hanaôgi (probably the second Hanaôgi) highlights her wisdom and cleverness. It is said that she was visited by a deputy of Nanbu han, who is said to have been too upright and righteous in the observation of his duties; his political rivals sent him to the Yoshiwara in the hopes that he would embarrass himself due to his lack of experience with the complex etiquette of the pleasure quarters. Unaware of, or consciously ignoring, how unusual it was to call directly upon such a high-ranking courtesan as Hanaôgi, he did so, and then explained to her his situation - namely, that his embarrassment would be the embarrassment of his lord and his domain - and asked her help, therefore, to avoid such embarrassment. The following day, his rivals called upon their favorite courtesans (their najimi, with whom they had a regular relationship), and expected that the Nanbu deputy would either have no one to call upon, or would call upon some call-girl of low rank or low quality, not knowing any better due to his backwoods inexperience. He then called on Hanaôgi, pretending in his backwoods ignorance and innocence to not know how high-ranking she was; her appearance stunned his rivals. Afterwards, the deputy, admitting his ignorance in the appropriate way to repay her, offered Hanaôhi fifty ryô; she insisted that she could not accept it, as her help had been freely offered and given, not bought, but realizing that the samurai's honor prevented him from taking back what he had offered, she had the money distributed among the staff and attendants. In the end, the deputy was not permitted to sleep with Hanaôgi, but enjoyed the services of her lower-ranking sister courtesans, and is said to have remained friendly with Hanaôgi, visiting her from time to time.[3]

Hanaôgi III became even moreso the talk of the town when, in 1785, she and her lover, hatamoto Abe Shikibu, attempted to commit a double love suicide[4] (though they failed, or were stopped). Though sympathy and romantic attitudes are said to have dominated public opinion earlier in the century, by this time, late in the 18th century, it is said that curiosity and contempt were among the dominant feelings expressed in reaction.[5]

Hanaôgi IV made her formal debut in 1787/4.[6] Her kamuro (child attendants) were named Tatsuta and Yoshino.[7]

In 1794, the current Hanaôgi of the time tried to escape from the Yoshiwara in order to elope with a man, but was caught and returned to the Ôgi-ya.

There were only a few periods in the late 18th to early 19th centuries when there was no active courtesan named Hanaôgi: 1797-1802, 1807-1811(?), and 1816(?)-1819. The last (probably ninth) Hanaôgi did not hold the same esteemed status as her predecessors; she was of the lower yobidashi chûsan rank, and had no shinzô attendants. She held the name from autumn 1839 until autumn 1842, after which Ôgiya Bunga, the fourth-generation owner of the teahouse, in part due to the extravagances of his grandfather Ôgiya Bokuga, was forced to sell the house.[8]

References

- Cecilia Segawa Seigle. Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan. University of Hawaii Press, 1993.