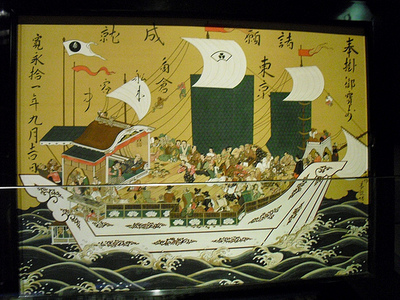

- Japanese: 朱印船 (shuinsen)

In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, merchants trading in Southeast Asia carried official permits, marking them as licensed traders and differentiating them from smugglers and pirates. These permits were stamped with a red seal (shuin), and as a result, the traders' ships came to be known as shuinsen, or "red seal ships."

The system was begun by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, but was further systematized under Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu, who appointed a bugyô (magistrate) to Nagasaki, and planned a system of governing foreign trade. He sought to guarantee (maintain) revenue from foreign trade while enforcing the ban on Christianity, and granted red seal licenses to daimyô and merchants who sought to engage in overseas trade.

In the time of the third Tokugawa shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu, the system was strengthened, adding the requirement of obtaining a hôsho, a second license or permission, from the rôjû (the chief shogunate elders), and addressed to the Nagasaki bugyô, granting the merchant permission to depart. This came after the realization by the shogunate that many of the shuinjô licenses given to foreign merchants were being used by daimyô or other high-ranking shogunate officials to engage in illegal trade; thus, the system had to be strengthened.[1]

Among the merchants who were granted red seal licenses and permission to engage in overseas trade, there were those who came to be known as the seven Great Red Seal Ship Families, who the shogunate remembered and appreciated. In Kyoto, these families included the Sueyoshi and Fushimi families, the house of Chaya Shirôjirô, and the house of Suminokura Ryôi. The son of William Adams also continued to enjoy "red seal" trading privileges, adopting his father's sobriquet, Miura Anjin.[1] Merchants frequently made offerings of ema (votive tablets) at Kiyomizu-dera before departing for Southeast Asia, in order to pray for a safe journey. Unlike the ema sold today at Shinto shrines, which are about the size of a postcard (though a good half-inch thick), these ema could be as large as several meters on a side.

The shuinsen (red seal ships) system ended, however, with the implementation of maritime restrictions in the 1630s-1640. By that time, roughly 350 licenses had been issued, including 43 to Chinese merchants and 38 to Europeans.[1]

References

- Gallery labels at Museum of Kyoto.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Marius Jansen, China in the Tokugawa World, Harvard University Press (1992), 18-19.

External Links

- Examples of red seal licenses to Luzon (Philippines) and Cochinchina (central/southern Vietnam), from a copy of the Gaiban Shokan (1818), National Archives of Japan.