Difference between revisions of "Yanagita Kunio"

| (6 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

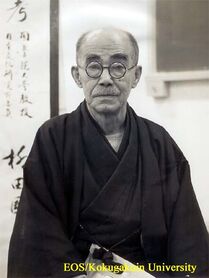

| + | [[Image:Yanagita_Kunio.jpg|thumb|209px|Yanagita Kunio]] | ||

* ''Born: [[1875]]'' | * ''Born: [[1875]]'' | ||

| − | * ''Died: | + | * ''Died: 1962'' |

* ''Other name: Matsuoka Kunio'' | * ''Other name: Matsuoka Kunio'' | ||

* ''Japanese'': 柳田 國男 ''(Yanagita Kunio)'' | * ''Japanese'': 柳田 國男 ''(Yanagita Kunio)'' | ||

| + | '''Yanagita Kunio''' was a scholar best known for his works in the fields of ethnology and folklore studies. He is often said to have been the founder of both of these fields within Japan, but others long before him had contributed to each, most notably Inoue Enryô and Minakata Kumagusu. His first and most well known work was ''Tôno monogatari'', a collection of folktales from the village of Tôno in [[Iwate Prefecture|Iwate]]. | ||

| − | + | ==Before Folk Studies== | |

| − | = | + | Yanagita (originally named Matsuoka Kunio) was born early within the [[Meiji Period]] in the year [[1875]], in a small village in [[Hyogo Prefecture|Hyôgo Prefecture]]. His father was a local physician, and Kunio was the fifth of eight children, the third of four surviving sons. Kunio's eldest brother had a failed marriage, and relocated to [[Tohoku|Tôhoku]] in search of a new life, while his second-oldest brother was adopted away into another family, as Kunio himself would be. Neither he nor his brothers continued their father's medical practice.<ref name=women191>Marcia Yonemoto, ''The Problem of Women in Early Modern Japan'', UC Press (2016), 191.</ref> He was quite well-read in Western literature as well as that of Japan and China, and it is likely that his attitudes toward folk studies stemmed from Western books concerning folklore and ethnology that he read during his formative years. Moreover, his father’s deep interest in the [[Kokugaku|National Learning]] movement instilled in him an appreciation for traditional Japanese faith and values in the face of what he called "foreign ways" and "newfangled affectations".<ref>Mori, 87.</ref> |

| − | Yanagita | + | After a childhood in which he was devoted to reading and literature, Yanagita received an education at Tokyo Imperial University in the field of agricultural administration, with the hopes that through this work he could improve the suffering and poverty of farmers. He was adopted in [[1901]] at the age of 26 by the Yanagita family, who saw in him a promising heir, based on his Tokyo Imperial University education and prospects as a government bureaucrat. Three years later, he was married to their fourth daughter, Ko. His new father-in-law, Yanagita Naohei, was a high court justice, and had many connections in the government bureaucracy. Though he came to have a rather successful life in many respects, Yanagita Kunio is said to have been perpetually treated as an outsider within his in-laws' family, and was given only a very small room in the house to use as his study.<ref name=women191/> |

| − | + | Soon after his adoption and marriage, he took a post at the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce as a bureaucratic inspector, traveling to various regions in Japan, and eventually becoming chief secretary of the Upper House. During this brief career Yanagita had been developing his attitudes and ideas concerning the common folk of Japan, and gradually these interests eclipsed in his mind the importance of agriculture, as it became clear that his ideas on the latter subject were gaining little support. | |

| − | Yanagita eventually found a position in the legislative bureau of the Japanese government, and in his free time traveled all around the country collecting folklore. His collections were not limited to folktales and legends, but also to folk beliefs and customs, which he divided into three categories: | + | Yanagita eventually found a position in the legislative bureau of the Japanese government, and in his free time traveled all around the country collecting folklore. His collections were not limited to folktales and legends, but also to folk beliefs and customs, which he divided into three categories:<ref>Mori, 92.</ref> |

* tangible culture | * tangible culture | ||

* linguistic arts, and | * linguistic arts, and | ||

| − | * mental phenomena [beliefs]. | + | * mental phenomena [beliefs]. |

==''Tôno Monogatari''== | ==''Tôno Monogatari''== | ||

| Line 27: | Line 29: | ||

==Minzokugaku== | ==Minzokugaku== | ||

| − | [[Image:Tabi_to_densetsu.jpg|thumb|110px|An issue of ''Tabi to densetsu'', "Travels and Legends".]]While Yanagita was not the first to study folk tales and beliefs, his work reshaped the approach to the field that largely still exists today. He believed that folklore and ethnology (民俗学 and 民族学, both ''minzokugaku'') were interesting and worthy of study in and of themselves, rather than for the purposes of their eradication or of their dissection for use in other fields such as psychology. His views dictated that by studying the strange, mysterious and fantastic elements of folklore, one could better understand the mindset and character of the everyday Japanese person of antiquity (and, presumably, of today); or in his own words, "the feelings of ordinary people in the past [''mukashi no bonjin no kokoromochi'']". | + | [[Image:Tabi_to_densetsu.jpg|thumb|110px|An issue of ''Tabi to densetsu'', "Travels and Legends".]]While Yanagita was not the first to study folk tales and beliefs, his work reshaped the approach to the field that largely still exists today. He believed that folklore and ethnology (民俗学 and 民族学, both ''minzokugaku'') were interesting and worthy of study in and of themselves, rather than for the purposes of their eradication or of their dissection for use in other fields such as psychology. His views dictated that by studying the strange, mysterious and fantastic elements of folklore, one could better understand the mindset and character of the everyday Japanese person of antiquity (and, presumably, of today); or in his own words, "the feelings of ordinary people in the past [''mukashi no bonjin no kokoromochi'']".<ref>Figal 113.</ref> In the course of his studies, he coined the word ''jômin'' (常民, "continuing man") to describe the sort of common folk that were the object of his interest. He felt that history in general was too concerned with broad strokes and trends -- "the ruling class and a number of heroes" -- , and not enough with the ordinary people. He also believed that the imagination of the Japanese folk was unrivaled in the world.<ref>Mori, 91.</ref> Modern folklorists believe that some of his views were flawed for various reasons, such as his assumption that there was an unchanging, universal character common to all Japanese in all regions and all times. Further criticism of Yanagita’s work stems from the suggestion that his ideas were merely subjective responses to the material he had studied. Regardless, Yanagita was the first to see such cultural value in the field of folk studies, and the present form of the field owes its current shape to his work. |

| − | The main importance of folk studies to Yanagita was uncovering the history of Japanese faith | + | The main importance of folk studies to Yanagita was uncovering the history of Japanese faith.<ref>Mori, 93.</ref> The means for him and his followers toward investigating these and other matters of folk belief were not through examination of historical documents and texts, but through firsthand collection of folktales and descriptions of customs and beliefs as told to him and others orally. |

| − | Yanagita established in 1928 a journal called ''Tabi to densetsu'' (旅と伝説, "Travels and Legends"), in which he outlined instructions to readers for traveling to countryside locations and collecting tales. Shortly after this, he published a guidebook for the same purposes, encouraging even more folktale submissions. After these early attempts at gathering tales, greater interest arose in his works, and through the sponsorship of the Japan Broadcasting Association, he and his students and colleagues such as Seki Keigo embarked on larger hunts for information, using as sources direct conversations with people like "rice farmers, deep-sea fishermen, and their wives" from "remote villages" | + | Yanagita established in 1928 a journal called ''Tabi to densetsu'' (旅と伝説, "Travels and Legends"), in which he outlined instructions to readers for traveling to countryside locations and collecting tales. Shortly after this, he published a guidebook for the same purposes, encouraging even more folktale submissions. After these early attempts at gathering tales, greater interest arose in his works, and through the sponsorship of the Japan Broadcasting Association, he and his students and colleagues such as Seki Keigo embarked on larger hunts for information, using as sources direct conversations with people like "rice farmers, deep-sea fishermen, and their wives" from "remote villages."<ref>Seki, viii.</ref> By 1935, several independent societies and institutes had formed with the goal of organizing similar collection efforts, most of which looked to Yanagita Kunio as their inspiration and authority. One of these was the Minzokugaku Kenkyûjo, or Institute for the Study of Japanese Folklore, which Yanagita himself established. While a great amount of material was collected by Yanagita's staff and students, he mostly limited the organization and analysis of these materials to himself in the early years.<ref>Mori 101.</ref> |

| − | == | + | ==Later Years== |

| − | Yanagita left his government position in 1920, and later that year traveled to Kyushu and Okinawa. In January 1921, he traveled around various parts of [[Okinawa prefecture]], and met with many of the fathers of Okinawan Studies, including [[Ifa Fuyu|Ifa Fuyû]], [[Higa Shuncho|Higa Shunchô]], [[Kishaba Eijun]], and [[Shimabukuro Genichiro|Shimabukuro Gen'ichirô]]. Following his return to the capital, he published articles about Okinawa in the ''[[Asahi Shimbun]]'', and gave a number of lectures. A lecture meeting held on April 21, called ''Nantô danwakai'' ("Southern Islands Conversation Meeting"), is of particular significance, as a great many notable scholars of the time were in attendance, including Kishaba Eijun and [[Orikuchi Shinobu]].<ref>Yokoyama Manabu 横山学, ''Ryûkyû koku shisetsu torai no kenkyû'' 琉球国使節渡来の研究, Tokyo: Yoshikawa kôbunkan (1987), 9-10.</ref> | + | Yanagita left his government position in 1920, and later that year traveled to Kyushu and Okinawa. In January 1921, he traveled around various parts of [[Okinawa prefecture]], and met with many of the fathers of Okinawan Studies, including [[Ifa Fuyu|Ifa Fuyû]], [[Higa Shuncho|Higa Shunchô]], [[Kishaba Eijun]], and [[Shimabukuro Genichiro|Shimabukuro Gen'ichirô]]. Following his return to the capital, he published articles about Okinawa in the ''[[Asahi Shimbun]]'', and gave a number of lectures. A lecture meeting held on April 21, called ''Nantô danwakai'' ("Southern Islands Conversation Meeting"), is of particular significance, as a great many notable scholars of the time were in attendance, including Kishaba Eijun and [[Orikuchi Shinobu]].<ref name=yokoyama>Yokoyama Manabu 横山学, ''Ryûkyû koku shisetsu torai no kenkyû'' 琉球国使節渡来の研究, Tokyo: Yoshikawa kôbunkan (1987), 9-10.</ref> |

| − | + | In May 1921, Yanagita took up a job with the Mandate Council (of which Japan was a member) at the League of Nations headquarters in Switzerland. Two years later, when he learned while in London of Tokyo's destruction in the Great Kantô Earthquake, he rushed home. Seeing the destruction, he was inspired to leave his League of Nations job and to devote himself more exclusively to scholarship. That December, he opened a Minzokugaku Symposium or Colloquium at his home. Scholars of Okinawan Studies, along with many others, regularly attended these gatherings. Along with Orikuchi, Yanagita began publishing essays describing Okinawa as representative of Japan's traditional past, or origins, and asserting that the study of Okinawan folklore could reveal much about Japan's history as well. Some of his essays, along with Orikuchi's, focused in particular on the notion that [[Ryukyuan religion]] represented an earlier or original form of [[Shinto]], indicative of just what ancient Japanese faith once was.<ref name=yokoyama/> | |

| − | In May 1921, Yanagita took up a job with the Mandate Council (of which Japan was a member) at the League of Nations headquarters in Switzerland. Two years later, when he learned while in London of Tokyo's destruction in the Great Kantô Earthquake, he rushed home. Seeing the destruction, he was inspired to leave his League of Nations job and to devote himself more exclusively to scholarship. That December, he opened a Minzokugaku Symposium or Colloquium at his home. Scholars of Okinawan Studies, along with many others, regularly attended these gatherings. Along with Orikuchi, Yanagita began publishing essays describing Okinawa as representative of Japan's traditional past, or origins, and asserting that the study of Okinawan folklore could reveal much about Japan's history as well.<ref name=yokoyama/> | ||

| − | Yanagita later took a position as an editor at the ''Asahi shinbun'' newspaper. During this time he criticized not only the fascism of Italy but also the militaristic and totalitarian feelings that were rising within his own country. He maintained that these values and morals of the imperial government were not the same as those of the common man. It can be said that in general, while Yanagita made a point of declaring his faith in the imperial system, he disagreed with many of the political and philosophical trends of the age. But any resistance he showed was carefully tempered, and he never put himself in a position that would endanger his career or livelihood. After retiring from the newspaper, he spoke no more about politics | + | Yanagita later took a position as an editor at the ''Asahi shinbun'' newspaper. During this time he criticized not only the fascism of Italy but also the militaristic and totalitarian feelings that were rising within his own country. He maintained that these values and morals of the imperial government were not the same as those of the common man. It can be said that in general, while Yanagita made a point of declaring his faith in the imperial system, he disagreed with many of the political and philosophical trends of the age. But any resistance he showed was carefully tempered, and he never put himself in a position that would endanger his career or livelihood. After retiring from the newspaper, he spoke no more about politics.<ref>Mori, 104.</ref> |

Throughout his later life, Yanagita remained for the most part somewhat active in folk studies, and in his lifetime he published a wealth of books on many different subjects within the field, which have been collected in Japan in a 36-volume set called ''Teihon Yanagita Kunio shû'' ("Standard Collection of the Works of Yanagita Kunio"). The vast majority of his work, regrettably, has never been translated into English. Yanagita Kunio died in 1962, aged 88. | Throughout his later life, Yanagita remained for the most part somewhat active in folk studies, and in his lifetime he published a wealth of books on many different subjects within the field, which have been collected in Japan in a 36-volume set called ''Teihon Yanagita Kunio shû'' ("Standard Collection of the Works of Yanagita Kunio"). The vast majority of his work, regrettably, has never been translated into English. Yanagita Kunio died in 1962, aged 88. | ||

Latest revision as of 20:26, 28 January 2018

- Born: 1875

- Died: 1962

- Other name: Matsuoka Kunio

- Japanese: 柳田 國男 (Yanagita Kunio)

Yanagita Kunio was a scholar best known for his works in the fields of ethnology and folklore studies. He is often said to have been the founder of both of these fields within Japan, but others long before him had contributed to each, most notably Inoue Enryô and Minakata Kumagusu. His first and most well known work was Tôno monogatari, a collection of folktales from the village of Tôno in Iwate.

Before Folk Studies

Yanagita (originally named Matsuoka Kunio) was born early within the Meiji Period in the year 1875, in a small village in Hyôgo Prefecture. His father was a local physician, and Kunio was the fifth of eight children, the third of four surviving sons. Kunio's eldest brother had a failed marriage, and relocated to Tôhoku in search of a new life, while his second-oldest brother was adopted away into another family, as Kunio himself would be. Neither he nor his brothers continued their father's medical practice.[1] He was quite well-read in Western literature as well as that of Japan and China, and it is likely that his attitudes toward folk studies stemmed from Western books concerning folklore and ethnology that he read during his formative years. Moreover, his father’s deep interest in the National Learning movement instilled in him an appreciation for traditional Japanese faith and values in the face of what he called "foreign ways" and "newfangled affectations".[2]

After a childhood in which he was devoted to reading and literature, Yanagita received an education at Tokyo Imperial University in the field of agricultural administration, with the hopes that through this work he could improve the suffering and poverty of farmers. He was adopted in 1901 at the age of 26 by the Yanagita family, who saw in him a promising heir, based on his Tokyo Imperial University education and prospects as a government bureaucrat. Three years later, he was married to their fourth daughter, Ko. His new father-in-law, Yanagita Naohei, was a high court justice, and had many connections in the government bureaucracy. Though he came to have a rather successful life in many respects, Yanagita Kunio is said to have been perpetually treated as an outsider within his in-laws' family, and was given only a very small room in the house to use as his study.[1]

Soon after his adoption and marriage, he took a post at the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce as a bureaucratic inspector, traveling to various regions in Japan, and eventually becoming chief secretary of the Upper House. During this brief career Yanagita had been developing his attitudes and ideas concerning the common folk of Japan, and gradually these interests eclipsed in his mind the importance of agriculture, as it became clear that his ideas on the latter subject were gaining little support.

Yanagita eventually found a position in the legislative bureau of the Japanese government, and in his free time traveled all around the country collecting folklore. His collections were not limited to folktales and legends, but also to folk beliefs and customs, which he divided into three categories:[3]

- tangible culture

- linguistic arts, and

- mental phenomena [beliefs].

Tôno Monogatari

The three texts that established Yanagita as a folklorist as well as the now dominant approach to folklore studies were Nochi no kahikatoa no ki, Ishigami mondō, and Tôno monogatari. Yanagita Kunio collected the tales that comprise the famous Tales of Tôno (遠野物語) in February of 1909 from local writer and fellow folklorist Sasaki Kizen (佐々木 喜善), alias "Kyôseki". The tales involved legends about the establishment of the area's three major kami, strange ghosts and creatures like kappa and yamanba, and many cases of mysterious phenomena such as kami-kakushi (神隠し), or abduction by the gods. The book was published in 1910, and it is one of the most well known of the early folklore texts books in Japan.

Yanagita was first and foremost concerned with collecting and preserving folk tales, although he did concentrate at times on interpretation, such as his lectures on tengu folklore (Figal 115). He believed in recording these tales in a curt, objective manner, exactly as they were told to him, without any personal embellishments. However, the stories collected from Kizen, who was himself a not only a folklorist but also a writer, were re-fashioned into Yanagita’s own tellings.

Minzokugaku

While Yanagita was not the first to study folk tales and beliefs, his work reshaped the approach to the field that largely still exists today. He believed that folklore and ethnology (民俗学 and 民族学, both minzokugaku) were interesting and worthy of study in and of themselves, rather than for the purposes of their eradication or of their dissection for use in other fields such as psychology. His views dictated that by studying the strange, mysterious and fantastic elements of folklore, one could better understand the mindset and character of the everyday Japanese person of antiquity (and, presumably, of today); or in his own words, "the feelings of ordinary people in the past [mukashi no bonjin no kokoromochi]".[4] In the course of his studies, he coined the word jômin (常民, "continuing man") to describe the sort of common folk that were the object of his interest. He felt that history in general was too concerned with broad strokes and trends -- "the ruling class and a number of heroes" -- , and not enough with the ordinary people. He also believed that the imagination of the Japanese folk was unrivaled in the world.[5] Modern folklorists believe that some of his views were flawed for various reasons, such as his assumption that there was an unchanging, universal character common to all Japanese in all regions and all times. Further criticism of Yanagita’s work stems from the suggestion that his ideas were merely subjective responses to the material he had studied. Regardless, Yanagita was the first to see such cultural value in the field of folk studies, and the present form of the field owes its current shape to his work.

The main importance of folk studies to Yanagita was uncovering the history of Japanese faith.[6] The means for him and his followers toward investigating these and other matters of folk belief were not through examination of historical documents and texts, but through firsthand collection of folktales and descriptions of customs and beliefs as told to him and others orally.

Yanagita established in 1928 a journal called Tabi to densetsu (旅と伝説, "Travels and Legends"), in which he outlined instructions to readers for traveling to countryside locations and collecting tales. Shortly after this, he published a guidebook for the same purposes, encouraging even more folktale submissions. After these early attempts at gathering tales, greater interest arose in his works, and through the sponsorship of the Japan Broadcasting Association, he and his students and colleagues such as Seki Keigo embarked on larger hunts for information, using as sources direct conversations with people like "rice farmers, deep-sea fishermen, and their wives" from "remote villages."[7] By 1935, several independent societies and institutes had formed with the goal of organizing similar collection efforts, most of which looked to Yanagita Kunio as their inspiration and authority. One of these was the Minzokugaku Kenkyûjo, or Institute for the Study of Japanese Folklore, which Yanagita himself established. While a great amount of material was collected by Yanagita's staff and students, he mostly limited the organization and analysis of these materials to himself in the early years.[8]

Later Years

Yanagita left his government position in 1920, and later that year traveled to Kyushu and Okinawa. In January 1921, he traveled around various parts of Okinawa prefecture, and met with many of the fathers of Okinawan Studies, including Ifa Fuyû, Higa Shunchô, Kishaba Eijun, and Shimabukuro Gen'ichirô. Following his return to the capital, he published articles about Okinawa in the Asahi Shimbun, and gave a number of lectures. A lecture meeting held on April 21, called Nantô danwakai ("Southern Islands Conversation Meeting"), is of particular significance, as a great many notable scholars of the time were in attendance, including Kishaba Eijun and Orikuchi Shinobu.[9]

In May 1921, Yanagita took up a job with the Mandate Council (of which Japan was a member) at the League of Nations headquarters in Switzerland. Two years later, when he learned while in London of Tokyo's destruction in the Great Kantô Earthquake, he rushed home. Seeing the destruction, he was inspired to leave his League of Nations job and to devote himself more exclusively to scholarship. That December, he opened a Minzokugaku Symposium or Colloquium at his home. Scholars of Okinawan Studies, along with many others, regularly attended these gatherings. Along with Orikuchi, Yanagita began publishing essays describing Okinawa as representative of Japan's traditional past, or origins, and asserting that the study of Okinawan folklore could reveal much about Japan's history as well. Some of his essays, along with Orikuchi's, focused in particular on the notion that Ryukyuan religion represented an earlier or original form of Shinto, indicative of just what ancient Japanese faith once was.[9]

Yanagita later took a position as an editor at the Asahi shinbun newspaper. During this time he criticized not only the fascism of Italy but also the militaristic and totalitarian feelings that were rising within his own country. He maintained that these values and morals of the imperial government were not the same as those of the common man. It can be said that in general, while Yanagita made a point of declaring his faith in the imperial system, he disagreed with many of the political and philosophical trends of the age. But any resistance he showed was carefully tempered, and he never put himself in a position that would endanger his career or livelihood. After retiring from the newspaper, he spoke no more about politics.[10]

Throughout his later life, Yanagita remained for the most part somewhat active in folk studies, and in his lifetime he published a wealth of books on many different subjects within the field, which have been collected in Japan in a 36-volume set called Teihon Yanagita Kunio shû ("Standard Collection of the Works of Yanagita Kunio"). The vast majority of his work, regrettably, has never been translated into English. Yanagita Kunio died in 1962, aged 88.

Some Well Known Publications

- Tôno monogatari ("Tales of Tôno")

- Shinto to minzokugaku ("Shinto and Folklore")

- Tengu hanashi ("About the Tengu"; literally "Tengu stories")

- Senzo no hanashi ("About Our Ancestors", literally "Stories of our ancestors“)

- Nihon mukashibanashi meii ("Yanagita Kunio Guide to the Japanese Folk Tale")

- Momotarô no Tanjô ("The Birth of Momotarô")

Other Materials

- Japanese Folk Tales, an English translation of Nippon no Mukashibanashi, a collection of Japanese folktales assembled by Yanagita Kunio, translated by Fanny Hagin Mayer. PDF file.

- Japanese Folk Tales, a separate edition of the above book, containing many tales not included in the earlier version. PDF file.

Sources

- Figal, Gerald. (1999) Civilization and Monsters: Spirits of Modernity in Meiji Japan. Duke University Press.

- Mori, Koichi. (1980) "Yanagita Kunio: An Interpretive Study". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. Nanzan University.

- Seki, Keigo. (1963) Folktales of Japan. University of Chicago Press.

- Mayer, Fanny Hagin. (1960) Japanese Folk Tales, translated from Nihon no mukashibanashi by Yanagita Kunio. Tokyo News Service, Ltd.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Marcia Yonemoto, The Problem of Women in Early Modern Japan, UC Press (2016), 191.

- ↑ Mori, 87.

- ↑ Mori, 92.

- ↑ Figal 113.

- ↑ Mori, 91.

- ↑ Mori, 93.

- ↑ Seki, viii.

- ↑ Mori 101.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Yokoyama Manabu 横山学, Ryûkyû koku shisetsu torai no kenkyû 琉球国使節渡来の研究, Tokyo: Yoshikawa kôbunkan (1987), 9-10.

- ↑ Mori, 104.