Difference between revisions of "Shunga"

m |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

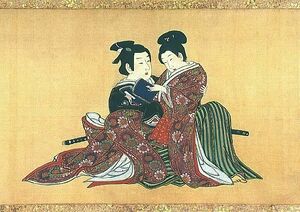

[[Image:Miyagawa Issho - Shunga emaki.jpg|right|thumb|300px|An early section from a ''shunga'' handscroll painting by [[Miyagawa Issho|Miyagawa Isshô]], c. 1750.]] | [[Image:Miyagawa Issho - Shunga emaki.jpg|right|thumb|300px|An early section from a ''shunga'' handscroll painting by [[Miyagawa Issho|Miyagawa Isshô]], c. 1750.]] | ||

| + | *''Other Names'': 笑絵 ''(warai-e)'' | ||

*''Japanese'': 春画 ''(shunga)'' | *''Japanese'': 春画 ''(shunga)'' | ||

| Line 11: | Line 12: | ||

''Shunga'' images also sometimes appeared within otherwise innocent guides to fashion, makeup, and hairstyling. | ''Shunga'' images also sometimes appeared within otherwise innocent guides to fashion, makeup, and hairstyling. | ||

| + | |||

| + | They were also referred to as ''warai-e'', or "laughing pictures," not because they were meant to be humorous, but with the meaning that they were set apart from the normal realm; they belonged to a cultural or conceptual space outside of the mundane realm of real-life propriety and duty.<ref>Jacqueline Berndt, “Manga and ‘Manga’: Contemporary Japanese Comics and their Dis/similarities with Hokusai Manga,” in ''Manggha'', Krakow: Japanese Art and Technology Center (2008), 7.</ref> While ''shunga'' or ''warai-e'' refers to the pictures themselves, or to single-sheet prints of such pictures, the terms ''shunpon'' (春本) and ''warai-hon'' (笑本) refer to books of such pictures. | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| Line 18: | Line 21: | ||

[[Isoda Koryusai|Isoda Koryûsai]], active a century later (c. 1760s-1780s), is considered one of the chief ''shunga'' designers of his time.<ref>Lane. pp111-114.; [[Anne Nishimura Morse|Morse, Anne Nishmura]] et al. ''The Allure of Edo: Ukiyo-e Painting from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston'' (江戸の誘惑: ボストン美術館所蔵 肉筆浮世絵展, Edo no yûwaku: Bosuton bijutsukan shozô nikuhitsu ukiyoe ten). Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun-sha, 2006. p182. </ref> | [[Isoda Koryusai|Isoda Koryûsai]], active a century later (c. 1760s-1780s), is considered one of the chief ''shunga'' designers of his time.<ref>Lane. pp111-114.; [[Anne Nishimura Morse|Morse, Anne Nishmura]] et al. ''The Allure of Edo: Ukiyo-e Painting from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston'' (江戸の誘惑: ボストン美術館所蔵 肉筆浮世絵展, Edo no yûwaku: Bosuton bijutsukan shozô nikuhitsu ukiyoe ten). Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun-sha, 2006. p182. </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Decline & Disappearance=== | ||

| + | The [[Meiji government]] issued an [[Ordinance Relating to Public Morals]] (''Ishiki kaii jorei'') in [[1872]] banning the sale or consumption of sexually explicit art. However, ''shunga'' fell into decline over the course of the [[Meiji period]] anyway, in part because of the rise of new forms of popular media, including photographs, and due to changing attitudes about fine art and high culture, among other factors.<ref>"[http://shunga.honolulumuseum.org/2014/index.php?page=5 Modern Love: 20th-Century Japanese Erotic Art]," Honolulu Museum of Art, exhibition website, accessed 1 Dec 2014.</ref> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Latest revision as of 23:44, 6 September 2015

- Other Names: 笑絵 (warai-e)

- Japanese: 春画 (shunga)

Shunga (lit. "spring pictures") is the term used to refer to ukiyo-e woodblock prints, woodblock printed books, and paintings of a graphic and erotic nature. Shunga was extremely common and popular in the Edo period, and, contrary to societal mores or expectations of today, were not very strictly censored, compared to, for example, images of a political nature. Also contrary to what we might expect or assume today, shunga artists were not separate from those who produced non-erotic images; in fact, a great many of the most famous ukiyo-e artists, known for their landscapes, bijinga, yakusha-e, or other non-erotic themes, also produced shunga. Shunga works include many of the most lavish examples of ukiyo-e - being printed on high-quality paper, and featuring the use of expensive pigments, materials such as silver, gold, and mica, and special techniques such as karazuri.

Some scholars have suggested a strong connection between the emergence of shunga and the significant samurai population of Edo as a result of the practice of sankin kôtai; according to this argument, shunga was created in parallel with the establishment of the Yoshiwara licensed pleasure quarters in order to satisfy the needs of these men for sexual release. Other scholars have countered this argument by pointing out that shunga was extensively produced in the Kamigata (Kansai) region as well, and that several kabuki plays suggest the popularity of shunga outside of Edo.

Meanwhile, regarding how shunga was enjoyed, or the reasons for its production, some assert that one of the chief roles or purposes of shunga was as a masturbatory aid. Others point to the numerous examples of shunga works which are generally believed to be guides for couples, girls' sexual education manuals, or works of a comical nature, as evidence against this argument. Further, they argue that shunga should be understood as being a part of the various genres of literature and publishing of the time, including didactic works, comical works, etc., rather than being severely separated out.

Many shunga works cited classical poetry or reimagined scenes from classical texts such as the Genji monogatari, or more recent stories such as those from kabuki plays; this was often done in a parodic or satirical mode, sometimes incorporating mitate, but the textual quotations of classical poetry or prose were also often cited directly, without alteration.

Shunga images also sometimes appeared within otherwise innocent guides to fashion, makeup, and hairstyling.

They were also referred to as warai-e, or "laughing pictures," not because they were meant to be humorous, but with the meaning that they were set apart from the normal realm; they belonged to a cultural or conceptual space outside of the mundane realm of real-life propriety and duty.[1] While shunga or warai-e refers to the pictures themselves, or to single-sheet prints of such pictures, the terms shunpon (春本) and warai-hon (笑本) refer to books of such pictures.

History

The so-called Kanbun Master (act. c. 1660s-1670s), whose name is not known, is generally regarded as one of the earliest and most prominent creators of shunga works.

Roughly one-quarter of the oeuvre of Hishikawa Moronobu, and roughly two-thirds of that of Sugimura Jihei, both active around the same time, consisted of shunga works.[2]

Isoda Koryûsai, active a century later (c. 1760s-1780s), is considered one of the chief shunga designers of his time.[3]

Decline & Disappearance

The Meiji government issued an Ordinance Relating to Public Morals (Ishiki kaii jorei) in 1872 banning the sale or consumption of sexually explicit art. However, shunga fell into decline over the course of the Meiji period anyway, in part because of the rise of new forms of popular media, including photographs, and due to changing attitudes about fine art and high culture, among other factors.[4]

References

- "The Arts of the Bedchamber: Japanese Shunga." Honolulu Museum of Art. Exhibition website. Accessed 24 November 2012.

- ↑ Jacqueline Berndt, “Manga and ‘Manga’: Contemporary Japanese Comics and their Dis/similarities with Hokusai Manga,” in Manggha, Krakow: Japanese Art and Technology Center (2008), 7.

- ↑ Lane, Richard. Images from the Floating World. New York: Konecky & Konecky, 1978. pp44-54.

- ↑ Lane. pp111-114.; Morse, Anne Nishmura et al. The Allure of Edo: Ukiyo-e Painting from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (江戸の誘惑: ボストン美術館所蔵 肉筆浮世絵展, Edo no yûwaku: Bosuton bijutsukan shozô nikuhitsu ukiyoe ten). Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun-sha, 2006. p182.

- ↑ "Modern Love: 20th-Century Japanese Erotic Art," Honolulu Museum of Art, exhibition website, accessed 1 Dec 2014.